The Devil Will Have His Due

Theatre Movement Bazaar’s Tiny Little Town

by Steven Leigh Morris

RECOMMENDED

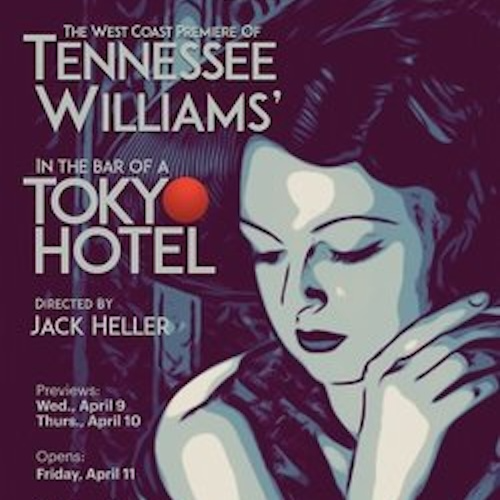

A physical theater troupe headed by choreographer-director-co-writer Tina Kronis and co-writer Richard Alger, Theater Movement Bazaar (which was birthed in New York City and relocated to LA in 1999) has spent the last quarter century mashing up world classics, crunching up texts and spitting them back via Kronis’s arch and often witty choreography. In their sights have been such writers as Tennessee Williams, Anton Chekhov and, in their current offering, Nikolai Gogol. The company could be seen as a descendent of The Wooster Group. In fact, both troupes have goofed off with F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

Theatre Movement Bazaar’s affinity with classical Russian writers in general, and Anton Chekhov in particular (Platanov, a riff on Chekov’s unfinished early play; The Seagull, spun from you-know-what; Track 3, based on The Three Sisters; Anton’s Uncles, spun from Uncle Vanya; Cherry Jam, a “jam” on The Cherry Orchard; you get the idea) led the troupe to perform at Moscow’s Gorky Drama Theatre in 2018. They’ve also performed in China, and are frequent visitors to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, where they’ve been regarded in the British press as one of the gems of Los Angeles theater.

You don’t need to take the Brits’ word for it. A visit to Hollywood’s The Broadwater on any Thursday through Sunday until February 18 should cement that point. Theatre Movement Bazaar’s Tiny Little Town is obviously an idea that’s been brewing. It first appeared in both 2017 and 2018 under the title The Inspector General, performed by students of the Los Angeles City College Academy.

Gogol’s The Inspector General (a.k.a. The Government Inspector) is the story of local officials in a small Russian town, dreading the arrival of an inspector from Moscow, whose job is to root out local corruption. Naturally, the town is dripping in corruption, and the local officials, including the mayor, are so paranoid that they mistake a visiting con artist for the inspector. This guy, who doesn’t pay his bills, is at first baffled and then delighted that the local officials are so willing to pay his way and ply him with cash. He leaves town in high style. Shortly thereafter, the officials are mortified when the real inspector general is on his way, recognizing with horror how soundly they had duped themselves.

Unlike many of the troupe’s other reinventions, Tiny Little Town is a fairly straightforward rendition of Gogol’s farce. Each character is rendered by only one actor. For this troupe, that’s revolutionary, or, perhaps reactionary. They call it a musical, with original music by Wes Myers (among this production’s stars) and lyrics by Alger, but it’s more of a play with music, threaded in large part by Kronis’s delightfully absurdist choreography that doesn’t let up through the entire production. The show features a blend of Broadway musical dance tropes and disco parodies, superbly executed by this ensemble of 12.

Disco? Yes, this Inspector General is relocated to small-town America, 1975, as Ellen McCartney’s costumes make abundantly clear, with jacket lapels and trousers flared as wide as satellite dishes. Meanwhile, some of the men’s sideburns float down below their ears. Among the production’s jokes is the con artist’s demand that his getaway car has an eight-track player.

Why 1975? I don’t know. I don’t mind. One effect is that it removes the play’s theme of relentless corruption from today’ partisan politics. Today’s politics are there for the taking, but they’re not imposed.

In 2016, South African director Sylvaine Strike’s Fortune Cookie Theatre Company relocated Moliére’s Tartuffe to the jazz era of the early 20th century. Her production (staged outdoors in Pretoria) was similarly broad physically, so that it too resembled a dance concert. It too provided no explanation, spoken or unspoken, about its era re-set.

Theatre Movement Bazaar’s local cousin is Matthew Walker’s Troubadour Theatre Company, a clown troupe that playfully riffs on musical styles, or albums, or artists of yore, though Kronis’s style is less improvisatory. The “Troubies” have dance numbers. This Tiny Little Town is danced-through.

One more local comparison: a spectacularly farcical rendition of The Government Inspector featuring Adam Haas Hunter as the con artist at Boston Court Theatre in 2012, directed by Stefan Nevinski. This was a co-production with the late and lamented Furious Theatre Company.

Shannon Holt and Adam Haas Hunter in “The Government Inspector” at Boston Court Theatre (co produced by Furious Theatre Company) in 2012. (Photo courtesy of Theatre @ Boston Court)

I confess to a feeling of apprehension upon viewing this production’s opening tableaux, with two clowns (Isaiah Noriega and Eddie Vona), attired in matching green jackets, boggle-eyed and grinning stupidly. As though impersonating puppets on a kids’ show, they kept re-setting a sign on an easel that told us the distance to “Tiny Little Town.” In each reset, the mileage from town got shorter, as though we were approaching this production’s eponymous locale.

The feeling in this viewer’s bones was that this might be okay, or we might be in for a very long two hours.

In retrospect, the experience was similar to listening to iambic pentameter in a Shakespeare play after one’s been away from verse plays for a bit. It takes a short while for the brain to wrap around the cadences, and to settle into a comfort level. As applied to Kronis’s choreography, initial misgivings about the physical humor segued into acceptance, particularly as the entire ensemble displayed not just competence but a skillful embrace of the farcical gestures. This was a production that evolved from that comfort level first to delight, and later to an intense mania by show’s end — a kind of terror that was the production’s point. When it comes to corruption, be careful of what you’re laughing at.

(This was also precisely the point of Sylvaine Strike’s rendition of Tartuffe, a world away.)

“Tiny Little Town”: Eddie Vona, Jesse Myers, Mark Doerr, Ishika Muchhal, Paula Rebelo, Kasper Svendsen, Prisca Kim (Photo by Doug Haverty)

At this production’s core is the self-important Mayor (Kasper Svendsen, with hair styled so that he resembles Bozo’s dad), his wife (Paula Rebelo, sharp as a whip and donning a perfect beehive wig that could easily source four jars of honey) and his daughter, Maria (the charming Ishika Muchhal). Local officials include the Health Commissioner (Mark Doerr), the Judge (Lamont Oakley), the School Superintendent (Jesse Meyers), the Postmaster (Joey Aquino) and the Real Estate Developer (technically not an “official,” but a strong presence nonetheless as portrayed by Prisca Kim).

In the antagonist camp is the conman, here named Konner (of course), and gently rendered by Nikhil Pai, who balances himself on a highwire between Konner’s desperate circumstances and ludicrously debonaire attempts to rise above them. The gold chains dangling from his neck tell you most of what you need to know about him. He has an accomplice (a formula borrowed from Tartuffe), a young guy here named Joseph who, in Nick Apostolina’s capable hands, straddles a a line between greed and conscience, particularly during Joseph’s fleeting romance with Maria.

This is a company with tuneful though not great voices, but they move like angels. No, they don’t move, they float.

Much of this production turns on Wes Myers’s music composition, fueled by jocular pop calypso and Eastern European rhythms, with ne’er a ballad in sight. A possible exception is one brief section of a duet between Joseph and Maria about being number two in life. But something extraordinary happens when the townsfolk realize that the real inspector (from Washington, D.C.) is en route.

The company had just been singing, somewhat defensively, about their corruption being merely an attempt to preserve a “good life” that means so much to them.

In a quick turn, the company is shrouded in a harsh front light (lighting design by Aaron Francis and Johnny Montage), while the music spins to the sound of harp playing what sounds like the allegro movement of a Vivaldi concerto. The harp then yields to a violin. In sound and music, or sound and fury, this does not signify nothing. It’s a complete shift in tone, from complacent farce into the kind of terror for which Nikolai Gogol made his name in writings such as The Overcoat and Dead Souls.

The devil is coming to take his due. And the devil is as eternal as corruption itself. This is no longer farce – it’s a cautionary tale bordering on a morality play. And all accomplished without a single lecture.

This Little Town is a fable not so much about a conman or his corruption. It’s about this town and its willingness, its eagerness, to be both corrupted and duped. If that doesn’t speak to our particular corner of history, I don’t know what does.

Theatre Movement Bazaar at The Broadwater, Hollywood. 1076 Lillian Way, Hollywood; Thurs.-Sat., 7:30, Sat.-Sun., 2:30 pm, thru Feb. 18. https://theatremovementbazaar.org Running time: Two hours with intermission.