The ensemble of Sweeney Todd (Photo by Craig Schwartz)

The Gripes of Wrath

Sweeney Todd at A Noise Within

By Steven Leigh Morris

RECOMMENDED

At intermission of director Julia Rodriguez-Elliott’s sumptuous production of Sweeney Todd at A Noise Within, I wandered by mistake into the theater’s donor lounge. There were clusters of people at tables, and I think I saw a gallery where they could see the stage, like box seats, or a private booth at a sports stadium. An usher approached me and stood in front me, blocking any forward motion on my part.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“I think I’m in the wrong place,” I replied. “What is this?”

“Do you have a check? he asked, brazen and sardonic.

“Will you take a rain check?”

In Act 2, I was back in my seat among the proletariat for this musical about a justifiably aggrieved barber, Sweeney Todd (Geoff Elliott), in Victorian London, having returned to Fleet Street after escaping from 15 years in prison, sentenced for a crime he didn’t commit. In his absence, his young wife Lucy (Amber Liekhus) was abducted, raped, and then abandoned by the judge (Jeremy Rabb) who sentenced him (a preview of Jeffrey Epstein’s tawdry and creepy sexual empire). Meanwhile, the same judge adopted the couple’s infant daughter, Johanna (Joanna A. Jones), as his ward, in the hope of marrying her as a teenager.

The Victorian London depicted in the 1979 Broadway hit by Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) and Hugh Wheeler (book) is one of obscene social stratification, a pre-Industrial Age in which the privileged flaunt the laws that are supposed to govern everybody. In response, a proprietor of a struggling pie shop, Mrs. Lovett (Cassandra Mary Murphy), discerns and acts on the idea that, with the help of the barber (adept at slitting throats while carrying a boulder of grievance on his shoulders), they can turn a handy profit from cannibalism, i.e. stuffing her meat pies with human flesh.

“The history of the world, my sweet, is who gets eaten, and who gets to eat.”

I mention the theater’s donor gallery not to be peevish. This is no different from first-class and economy seats on an airplane, or a members’ lounge at an airport. There’s no whiff of corruption in this, or even injustice. But it is an emblem of social stratification, nonetheless. You are proffered a special place, first, if you want to pay for it, and second, if you can afford to pay for it. And that’s where the slippery slope begins.

Sweeney Todd is populated by a large number of people in rags, and broken teeth, and no health care, while the world-weary Judge Turpin sentences one such wretch to “hang by your neck until you are dead,” for some petty theft.

In England, privilege was bestowed from blood lines. In the U.S., there’s some of that, but it’s mostly bestowed from wealth, stemming from a national creation myth — a half-truth which says that anybody with wits and guile can join the ranks of the wealthy. This myth is a source of inspiration and solipsism, while also being diabolically cruel to those who discover that here, like almost everywhere else, the odds of social mobility are stacked against the poor.

A Noise Within’s donor lounge is a form of social stratification that’s systemically built into an institutional theater, reflecting an economic caste system well beyond this theater’s doors. I can’t tell if it’s savvy, clueless, or both, like a Broadway theater charging $300 a ticket for a musical depiction of the French Revolution in Les Misérables — “Justice! Equality! Fraternity!” — and then selling $65 T-shirts in the lobby emblazoned with the faces of the French proletariat. Rich.

Glorifying revolution, however, is not the point of Sweeney Todd. Rather, its point is quite the opposite. The musical derives from numerous literary sources, while its theatrical origins date back to ancient Greek, Shakespearean and Jacobean warnings against revenge as a substitute for justice. Vengeance is Sweeney Todd’s undoing, though his fury is righteous, just as vengeance causes the unraveling of King Creon in Antigone, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, King Lear and Thomas Middleton’s Vindice (the avenger in Middleton’s 1606 A Revenger’s Tragedy).

BACK TO THE FUTURE

How does all of this apply to our little corner of history, in 2024?

Social stratification, via the growing inequities in the distribution of wealth and social services, has become increasingly pronounced in the U.S. since Sweeney Todd’s 1979 premiere.

According to Stastica, “In the third quarter of 2023, 66.6 percent of the total wealth in the United States was owned by the top 10 percent of earners. In comparison, the lowest 50 percent of earners only owned 2.6 percent of the total wealth.”

(Perhaps you’ve been wondering where all those homeless people come from.)

Meanwhile, “The top 20% of Americans by income have seen their share of wealth increase the most between 1990 and 2022. In the final quarter of 2022, this group held 71% of the nation’s wealth – up from 61% in 1990.” (This is from Facts: USA)

Facts such as these lead directly to the slippery slope of what people choose to spend their income on, what they can actually afford (members’ lounges at airports and donor lounges in theaters) and where they’re being iced out.

The stakes for a democratic republic, such as ours, continue to rise when one considers both the growing power of small clusters of the mega-wealthy in the U.S., like the nobility and landed gentry in Victorian England, and their disproportionate influence over social policy, such as their growing influence on institutions such as the U.S. Supreme Court. The latter takes us back, directly, to Sweeney Todd’s Judge Turpin — an embodiment of corruption woven into the power structure.

From The Guardian in August, 2023: “The billionaire hedge fund manager Paul Singer is chairman of the Manhattan Institute and Kathy Crow, who is married to the real estate mogul Harlan Crow, serves as a trustee of the group. Both have provided two of the justices — Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, respectively — with private travel gifts and have socialized with the judges on lavish vacations, according to reports in ProPublica and other media outlets.”

Sweeney Todd doesn’t delve into the politics of Judge Turpin, such as who bribes him, and how. Rather, one can infer that the corruption in Victorian London is akin to the crony system in modern Russia. Our political corruption is more sophisticated.

“What makes American oligarchy different from its Russian counterpart is that it operates at significantly greater arm’s length, driven by lobbying and campaign contributions rather than outright corruption,” Jamie Lowe explains in an August 2023 article in the New York Times Magazine.

Lowe lays out a case for how a tiny fraction of U.S. billionaires is helping determine public policy in their own interest, and in defiance of public will. His survey stems from research by three political scientists at Northwestern University: Benjamin Page, Nathan Seawright and Matthew LaCombe.

The outsized influence of a handful of billionaires is a direct assault on core principles of a functioning democracy, and lands us on the cusp of Sweeney Todd’s callously indifferent and authoritarian England.

According to Lowe, 40% of all political donations come from the top 1% of the top 1%.

“Though the billionaires barely showed up in the public record talking about taxes, for example, it was still possible to connect their sizable contributions to ideological political action committees and to candidates who supported issues like tax cuts for the wealthy, privatizing Social Security, reduced social spending and abolishing the estate tax. ‘What we see basically is a class of people who have more money than God, who are very politically active in relatively unknown ways and who we have reasons to believe have been politically influential and have used their political influence in ways that don’t really serve the interests or preferences of what most Americans want,’ Lacombe says.”

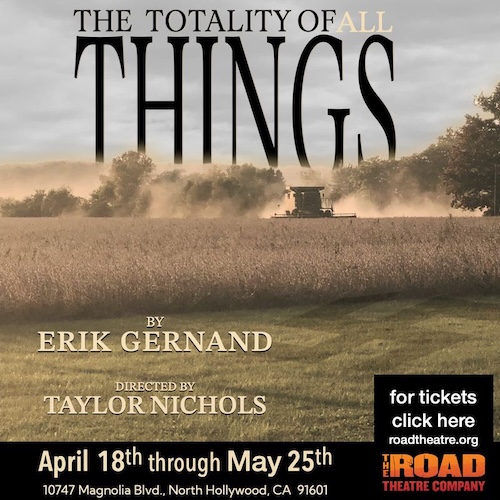

Sweeney Todd at A Noise Within

Julia Rodriguez-Elliott has been directing for a long time, and that experience comes blazing through in her artful direction that knocks the stage floor all the way back to the rear theater wall. This makes for an open and cavernous playing space framed by a, yes, Victorian proscenium arch (set by Francois-Pierre Couture). Rows of Gothic theater seats face the audience at the production’s start. These are soon populated by the 17-member ensemble (Gads, this is an expensive production!) who sing the opening chorale from those seats, before they (seats and actors) roll away to be replaced by set pieces such as looming, rolling step-ladders that permit Judge Turpin’s ward Johanna to be perched in her cage high above the action; and for her suitor, Anthony (James Everts) to romance her from across the stage, also at an elevation. The placement of the actors, using depth and height, is as beautiful and carefully considered as a series of paintings, supplemented by Tony Valdes’s ghoulish makeup.

Rod Bagheri’s musical direction takes Sondheim’s lush orchestrations and scales them back to a pair of pianos and a cello. Furthermore, the pianos are spinets that have an almost honkey-tonk tone, sending the musical accompaniment to Sondheim’s quasi-operatic score into a 19th century music hall. Given the rich and robust voices among the ensemble, I found the juxtaposition of voices and accompaniment to be both apt and moving.

Joanna A. Jones’s soprano Johanna is, almost literally, a songbird. The most ornate cadenzas spill out effortlessly. One can see her acing “The Queen of the Night” aria in Mozart’s The Magic Flute.

Cassandra Marie Murphy’s Mrs. Lovett is way too young (she was operating a pie shop 15 years before the present action, and she appears now to be in her mid-30s, which would have her starting a pie-shop business in London at the age of about 15.) Compensating for this lapse in verisimilitude is her vocal dexterity and split-second timing.

Josey Montana McCoy and James Everts are perfect, musically and stylistically as, respectively, Mrs. Lovett’s helper Tobie and Johanna’s suitor, Anthony, sharing the virtues of Kasey Mahaffy’s huckster Pirelli.

Amber Lekhus turns in a solid and credible performance as the Beggar Woman. Ditto Harrison White as Beadle Bamford, though the latter’s voice is comparatively thin.

And the gangling Jeremy Rabb is a striking presence as Judge Turpin; his song interpretations are equally striking.

For all this beauty and skill, there’s an enigma at the heart of this production in Geoff Elliott’s Sweeney Todd. He has a thundering basso profundo that he releases sporadically, at times keeping it under wraps, curtailing musicality when melody is called for. I honestly couldn’t tell if it this is a choice or an idiosyncrasy.

His physicality is commanding while being understated. “His skin was pale and his eye was odd,” the ensemble tells us. That “odd eye” (as though placed slightly higher than the other) is there, as though the manifestation of an understandable mental condition. A rage festers beneath words and perhaps beneath gestures. Those physical aspects are really quite brilliant.

And yet, vocally, that resonant and obviously trained voice wavers, literally. It arrives in waves, halting, even in moments of epiphany, holding up his shaving knives, “At last, my arm is complete again!”

Again, I couldn’t determine if this is an actor’s technique, or an actor’s idiosyncrasy, and I spent so much time trying to unravel this mystery that I was blocked from leaping into the character’s tortured soul — thereby imposing onto Sweeney Todd the characteristics that defined him rather than receiving those characteristics from him.

That said, this is a lavish production, and days later, I still can’t get those intersecting fugues, those sweeping, crashing, racing harmonies out of my head.

Nor the resonance and relevance of all that this musical continues to portend.

SWEENEY TODD: THE DEMON BARBER OF FLEET STREET | By Stephen Sondheim and Hugh Wheeler | A Noise Within, Foothill Blvd., Pasadena. Fri.-Sat., 8 pm, Sat.-Sun., 2 pm, Thurs., 7:30 pm; thru March 17. www.anoisewithin.org 1 hour and 45 minutes, including intermission.