Apocalypse Now

How “Waiting for Godot” at the Geffen Meets This Cultural Moment

RECOMMENDED

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, currently in a production that works fitfully at Geffen Playhouse, may be the 20th century’s Hamlet. These are plays of cosmic scale that hold within their grasp the entirety of human endeavor. Godot speaks to our times perhaps more clearly than it did to its own, which was the mid 20th century, when it was first presented. It was part of the Theatre of the Absurd movement that responded collectively to the U.S. dropping of atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan, and the first realization by humanity, pre-climate change, that we are fully capable of destroying ourselves entirely, and for no good reason. Hence, the entire Theatre of the Absurd, like Waiting for Godot, trafficked in a kind of vaudevillian frivolity against the threat of the planet going up in flames.

I was in graduate school when, at the tail end of the 1970s, then-Governor Ronald Reagan was elected President, and I recall one of my UCLA theater professors opining that the Theatre of the Absurd was a dead genre. And yet . . . Look at our world now. Look at our country. From the number of productions of Waiting for Godot across the globe, it’s evident that its prescience and pertinence have roared back (assuming they ever left), along with the genre it was a part of.

When Hamlet stabs his girlfriend’s dad, Polonius, by mistake, he sets off a chain of melodramatic repercussions. Suddenly, a play with events but no discernible stage action (like Waiting for Godot) takes on a devastating kind of propulsion and plotting that leads to an apocalypse. Almost everybody dies in Hamlet for no good reason, with the exception of Hamlet’s best friend, Horatio, the designated historian; and some newcomers: the Ambassador from England, and the invading Prince of Norway who’s a bit stunned to arrive into a palace so populated with corpses. And what is the reason for this carnage? Vengeance. Spite.

It would be a platitude to point out that the apocalyptic vengeance and spite that motivate our newly arriving administration in Washington, D.C., is very Hamlet-like, so I won’t, even though I just did. Just pretend you didn’t read it.

Furthermore, much of Hamlet and Waiting for Godot consists of the characters trying to discern what is real, and what isn’t. With the prevalence of unfiltered social media, and world-wide webs light and dark, this is a particularly 21st century conundrum. For Hamlet, that question (what is real?) is tied to the criminal intent of his Uncle Claudius. Hamlet derives from the ghost of his father a conspiracy theory aboiut his dad’s somewhat mysterious death. The ghost tells Hamlet how Claudius took his life and his wife, though Hamlet is not entirely sure that this ghost is really his dad. Perhaps he’s an agent of the devil, aiming to trick him; it could be argued that Hamlet has entered R.F.K., Jr./Marjorie Taylor Greene territory, but Hamlet is smart enough to avoid leaping to lunatic conclusions, as our contemporary political clowns do, or seem to. (Who knows what they really believe.) Rather, with the lack of DNA technology, Hamlet turns to the theater to discern what is actually going on. He turns to a troupe of touring thespians. This is to gauge the reactions of the culprits to a play-with-the-play that dramatizes the ghost’s story. “The play’s the thing to catch the conscience of the king,” Detective Hamlet theorizes.

The theater reveals the truth. That’s why theater-people so love Hamlet. This is something to keep in mind as we head into the bleak tunnel of 2025 that’s populated with fools, sadists, and bigots, whose aim is to control our lives and otherwise punish us. For what, I’m not sure. That, and their other aim: vengeance. It’s somebody’s fault that the price of eggs has risen. It doesn’t matter who. Let’s hang somebody, anybody, before burning down the place.

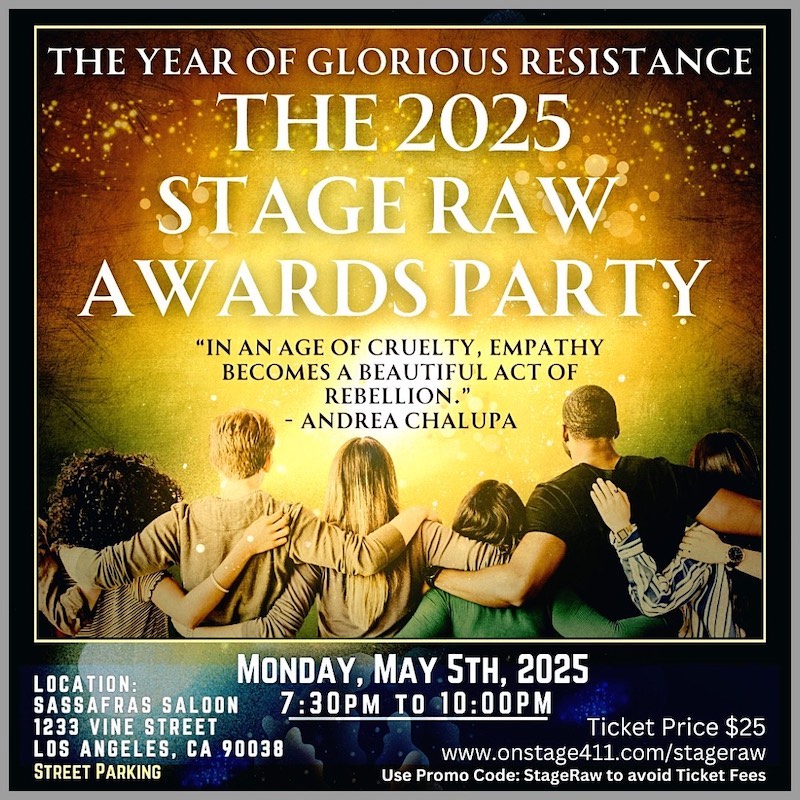

Can our theater rise to the occasion, as a force of resistance to this lunacy, and to fathom what is actuallygoing on, who is actually pillaging the kingdom, the way Hamlet’s itinerant troupe did; the way Czech theater did with playwright Vaclav Havel, in the 1980s? Havel’s comedies, mocking his communist government’s bureaucratic cruelties, landed him in a jail cell. The government that put him there imploded from its sadistic overreaching, and Havel walked out of prison to become president of the country — elected, not appointed. In 1990, Havel spoke before the U.S. Congress, warning of authoritarian trends and the dangers to democracy posed by Russia, despite then-President Mikhail Gorbachev’s pro-democracy leanings at that time, contrasted against Vladimir Putin’s czarist impulses today. Look at them now. And look at us now. How quickly things can turn.

A tendency of those in power is to diminish theater people as a tribe that lives in a land of make-believe. The current president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, is also a man of the theater (a stage and TV actor), ridiculed by his Russian adversary Putin for being so.

In fact, some of the bravest characters in world history have come from the theater. They are people who know very well what’s real and what isn’t. It’s an utterly depressing paradox that it takes toxic, bully governments to give theater its relevance. I’d rather live in tranquil times where the theater can afford to be less relevant. But that’s not what we’re facing in the next few years.

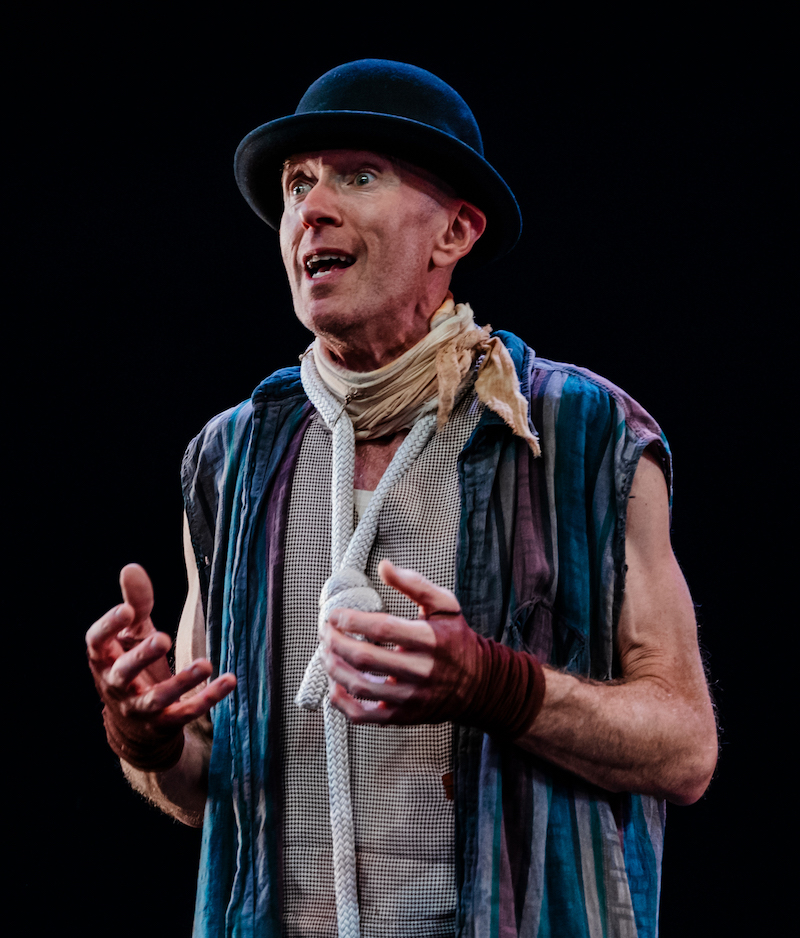

Rainn Wilson, Aasif Mandi, and Adam Stein in “Waiting for Godot” at the Geffen Playhouse. (Photo by Jeff Lorch)

As in Hamlet, Godot’s clown duo, Vladimir and Estragon (Rainn Wilson and Aasif Mandi), spend most of Beckett’s play trying to figure out what on Earth is going on? For V and E, that question is tied to existential questions of how they came to their plight. Who is in charge? Should they leave the desert in which they’ve landed? Should they stay? Should they go? And if they go, should they do so together or apart?

Unlike in Hamlet, there’s no vengeance in Waiting for Godot, but there is a pair of clowns struggling, like Hamlet, to fathom what’s real and what isn’t, which is their challenge within their worlds; it’s also our struggle in this false-intel, hate-filled corner of history. While waiting for instructions from an offstage figure named Godot (who never shows up) — the details of which . . . well, there are no details. While waiting, the two clowns are “entertained” by a pair of visitors: A whip-bearing, sadist Pozzo (Conor Lovett) and his slave, Lucky (Adam Stein). And there’s “all humanity,” to quote a line from the play. Pozzo is en route to sell at market his wrung-dry-by age-and-abuse slave. (“He used to dance the Fandango” Pozzo recalls, wistfully.) Pozzo throws Estragon and Vladimir a couple of vanquished chicken bones, which they gleefully inhale (our distribution of wealth), and with rope and whip, the travelers depart. A Boy (Lincoln Bonilla at the performance I attended) arrives, a delegate of Godot, to inform the clowns that Godot will not be coming today but will surely come tomorrow. The sun goes down on their barren landscape, hues of black and white, containing a single, skeletal silver tree. (Set design by Kaye Voyce). And with the help of Simon Bennison’s gentle, austere lighting, the moon slowly emerges like a headlight shrouded in haze.

The next day (Act 2), if it is the next day (an open question), we see much the same repartee repeated, as the clowns try to fathom what they should do while waiting. They already tried hanging themselves, that didn’t work. They could turn “resolutely toward nature,” and the beauties thereof, which would be swell if they weren’t gazing out upon the end of the world. Compounding these events is the slippage of memory. Did what happen yesterday actually happen? Has time stopped? This could be a portrait of singular dementia or collective amnesia, as the planet chokes on the fumes we’ve invented and belched into the stratosphere with such technical expertise, as history itself winds down. What is the point of remembering? For whom? For what?

Pozzo and Lucky return from the direction they departed in Act 1. Pozzo is now blind and deaf. “One day we go blind. One day we go deaf.” What day? What difference? One day we are born. One day we shall die. The same day. Pozzo collapses into a heap, crying out for help, while Vladimir and Estragon prevaricate whether or not it’s possible or necessary to help him get back on his feet. This, to me, from a moral standpoint, is the most blistering scene in the play. Should we help Ukraine or Gaza? Hmmm. Let’s think this over, pontificate, let’s look at all the arguments, pro and con. It’s like a portrait of the squabbling at the United Nations and in our own national Congress, while famine and fury blister entire regions of the world. “Help” cries Pozzo repeatedly, from his heap, while they dawdle. And when they finally do take action, they get pulled down to onto Pozzo’s level.

Godot has become one of most widely produced classics in recent memory. It is so familiar to theater afficionados that, like Hamlet, any production slams into an array of pre-conceived notions of what it should be, with its biggest admirers able to mouth its every turn-of-phrase along with the actors.

That said, I had difficulty absorbing Mandvi’s high-pitched Estragon, with all due respect to the actor’s mastery of timing and comic technique. It’s just a predisposition, an expectation that director Judy Hegarty Lovett’s quite beautiful and oft-lugubrious production breached. One should be open to variations to the play’s musicality. That’s what new productions are for. But Mandvi’s pitch triggered in me discomfort that I couldn’t overcome, and I have no valid explanation as to why.

Hegarty Lovett’s staging refused, as though in defiance, to exploit the rapid-fire repartee that marks this play’s vaudeville duo traditions: Laurel and Hardy, Abbot and Costello, The Smothers Brothers. Hegarty Lovett was in no rush to comply with such expectations, and her confidence in that decision gave her production its authority.

One scene in particular comes to mind, when the duo has physical shtick, written into the play, of swapping hats, back and forth, until the image is one of juggling. It has no point, and therein lies its pointless stupidity and charm. Hegarty Lovett stages that action in slow motion. For the same reason I can’t explain why the high pitch of one actor’s voice bothered me, I similarly can’t explain why I found this slowed down sequence of physical farce to be so beautiful. We all have a nervous system, and such revisions land differently upon each of us.

Similarly gorgeous to me was the stark production design in mostly black and white, and how the transitions between day and night slithered in, imperceptively. Add to that Mel Merceir’s subliminal sound design of a rumbling chord that played behind entire scenes of dialogue, adding a sense of eeriness to what’s traditionally imagined as an existential comedy.

Waiting for Godot is, in many ways, a very funny play, but director Hegarty Lovett is determined, to her credit, to underscore how its larger point is no laughing matter.

Last night, I watched an old clip from the Johnny Carson show. And the Smothers Brothers were the guests. And Tommy Smothers, with a similar child-like energy to Mandvi’s Estragon, made a heartfelt announcement that the prior night, his wife had given birth to healthy boy. And the crowd roared in loving applause until his brother, Dick Smothers, sitting next to him, piped, in, “Tommy, that’s not true. You know that’s not true. Your wife did not give birth last night. Why would you say something like that, just for applause?”

And Tommy Smothers replied, “Well, if you hadn’t said anything, ruined it, it could have been a lovely moment.”

“But why would you say something like that?” Dick countered. “Why would you lie?”

Tommy thought it over for a moment: “National policy.”

That was 1974. The difference is, 50 years later, if he were called out on such a lie, it wouldn’t make a jot of difference. If he’d been credibly charged with sexual assault, people would still vote for him.

We’re living in a second rate carnie show, where the values on which most of us were weaned – almost biblical edicts (tell the truth, treat your neighbor like yourself, be as kind as you’re able, help those in need) – are derided by our newcomers to national power as naive, or mocked for no reason at all: “Your body, my choice.”

The lyrics in Joni Mitchell’s adaptation of T.S. Eliot’s poem, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” are more true now than ever.

“Innocence is drowned in anarchy.

“The best lack conviction . . .

“And the worst are full of passion

“Without mercy.”

We’re still lodgers in Plato’s cave, seeing only shadows on the cave wall and trying, like Beckett’s characters in Waiting for Godot, to discern what is real, and what is not.

The Theatre of the Absurd is upon us once more.

The Geffen Playhouse, 10886 Le Conte Ave., Westwood; Wed.-Sat, 8pm, Sat., 3 pm, Sun., 2 pm; thru Dec. 15, www.geffenplayhouse.org. Running time: Two hours and 30 minutes, including intermission.