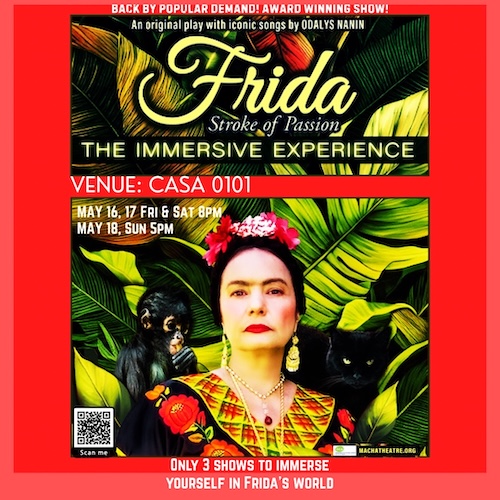

Frances Fisher and Joe Cortese as Linda and Willy Loman, in Death of a Salesman at the Colony (Photo: Billy W. Bennight, II)

Arthur Miller, Our Theater’s Nostradamus

Death of a Salesman at the Colony Theatre

I know it may sound funny, But people ev’rywhere are runnin’ out of money

We just can’t make it by ourself.

It is cold and the wind is blowing, We need something to keep us going

Mr. President, have pity on the working man.

Maybe you’re cheatin’, Maybe you’re lyin’, Maybe you have lost your mind

Maybe you only think about yourself. . .

— Randy Newman from the album Good Old Boys, released September, 1974

In his single, “Mr. President (Have Pity on the Working Man),” Randy Newman was referring to Republican President Richard Nixon at a time when the Democratic Party still held the loyalty of America’s working class. Some 50 years later, that loyalty has switched political allegiances, thanks in part to the globalism and neo-liberalism of the 1990s, embodied by Democratic President Bill Clinton, and compounded by the collapse of our free press, libertarian billionaire owners of social media, and a decades-planned takeover of courts and congresses across the land by the likes of the Federalist Society and mega-wealthy influencers such as the Koch Brothers. Neo-Liberalism and globalism strengthened the American economy, Wall Street and the upper class, while they, and the technologies that came with them, helped to deplete our middle class and leave the working class in the dust, as the nation’s wealth was increasingly concentrated at the top. The robust pension plans, health care, labor unions and other life-support systems that were part of American industrial base in post-Great Depression America, were eroded to a threadbare blanket by countless variations on Ronald Reagan’s trickle-down theory.

Gilded ages of obscene wealth in the hands of very few, at the expense of the many, resulted in lunatic and violent revolutions in France and Russia, in the 18th and 20th centuries, respectively. In the wake of the unregulated greed-fest that resulted in the 1929 stock market crash and America’s Great Depression, perhaps such European mob violence was on Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s mind when he created Social Security and other federal safety net programs to shore up the American work force. I don’t know if that was also on LBJ’s mind when he tried to use the federal government to wage a war on poverty in the hinterlands and inner cities, or on President Joe Biden’s mind when he tried to rescue college students from predatory loans, after they’d paid back what they’d borrowed, with interest, yet remained on the hook often for much the same amount as they initially borrowed. These were presidents, and actions, aimed at saving capitalism from itself.

Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, the Robin Hoods of our Sherwood Forest, have engaged in a Quixotic fight not just against the unelected oligarchs who are now so transparently running the country, but also against the capitulation, if not complicity, of so many of their Democratic colleagues.

With the richest men in the world on the dais of Trump’s inauguration, where state governors used to sit, we have officially entered what many of us realized a decade ago, and what Warren and Sanders have been saying until blue in the face — that we no can no longer function as a democracy within the confines of yet another gilded age, the likes of which we haven’t seen on our shores in a century.

Freezing temps moved Trump’s 2025 inauguration and its parties indoors. Trump voters from Arkansas and Oklahoma shelled out for price-gouged D.C. hotel rooms to celebrate the rite but couldn’t get in. Rather, they had to watch it from TVs in their hotel lobbies. They understood that they might as well have stayed home. Perhaps one day, they’ll understand the symbolism in those blasts of cold wind that kept them away from the party to which they imagined they’d been invited.

Playwright Arthur Miller could see all this from his perch in 1949, when what was to become his most internationally produced and highly regarded play, Death of a Salesman, opened on Broadway.

He was accused of being un-American. A combination of factors contributed to this: In 1956 and 1957, he was subpoenaed to “name names” of “communist” colleagues before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House on Unamerican Activities Committee. He refused to do so and was convicted of Contempt of Congress. (That conviction was overturned on appeal the year after it was invoked.) Then there were his plays, A View from the Bridge and Death of a Salesman. The former took an empathetic look at undocumented (Italian) immigrants to the United States, who were facing precisely the kinds of deportation policies being instituted in January 2025. But the latter, now being produced by Panic! Productions at the Colony Theatre, cuts to the quick.

Two stories converge: that of a father and that of a son. Based in 1949 Brooklyn, the patriarch, Willy Loman (Joe Cortese), suffers from the delusion that his labor as a salesman (which includes hours-long work driving up and down the Atlantic seaboard to meet buyers) should be a source of pride and wealth. It is neither. He may have been a hot shot salesman in years-gone-by, as he brags (hard to tell what’s true, since he’s an unreliable source of ramblings and contradictions), but now, at the age of 63, even he admits that in Massachusetts and Connecticut towns, the people who might have known him are now all dead. Once, he was on salary. Now he works entirely on commission. And even that arrangement is on the line.

Nor are either of his sons moving up the financial or class ladder. Philanderer and serial liar Harold (or “Happy,” Robert Smythe) works as one of two assistants to an assistant warehouse manager. His main source of pride is seducing executives’ fiancées. His older brother, Willy’s prodigal son, Biff (Cronin Cullen), a lifelong kleptomaniac, is “still finding himself at the age of 34.” At the start of the play, Biff has returned home after one of his many sojourns to western states, working as a farmhand and a ranch hand, and landing himself in jail multiple times for his petty thieving. Biff finds the prospect of working in the city to play the game of success a suffocating proposition. Yet he agrees to do so, for the sake of his mother, Linda (Frances Fisher), since his father is showing signs of mentally unravelling.

Full of bluster, Willy and Happy are obsessed with success, as defined by wealth and social climbing. They are both delusional. This is hardly a ringing endorsement of the American Dream, and the drama critics of 1949 pounced on Miller for this, blaming the entire Loman family for being reprobates rather than embracing Miller’s indictment of a broken system. He was nonetheless defended by Lillian Hellman, who argued that the Lomans’ next door neighbors, Charlie (Gary Hudson), and his nerdy son, Bernard (Brian Guest) are actually an embodiment of the American Dream. Jocular Charlie, perpetually “lending” Willy money to pay his bills (his source of funds remains a mystery), is as cavalier and unconcerned about his status as Willy is obsessed by it. Meanwhile, Bernard tries to leak exam answers to Biff in high school, yet Bernard is himself a focused scholar, graduating from law school and eventually pleading a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. In a telling moment, Willy has a scene with Bernard, who mentions nothing of this accomplishment. When Charlie later fills him in, Willy can’t understand why Bernard didn’t mention it. “He doesn’t need to,” Charlie replies. “He’s doing it.”

Meanwhile, Biff and Happy “treat” their father to a celebratory dinner — honoring Biff’s (unfounded) new business proposition to a former schoolmate. A glamorous woman (Michelle Jasso) slithers in and, at Happy’s urging, cancels her plans and invites a female friend (Jennifer Olsberg) to accompany her, and the two young men, to a night on the town, leaving Willy babbling to himself in the restaurant’s toilet.

“I don’t say he’s a great man,” Linda lectures her sons, on hearing this news while bursting with fury. “Willy Loman never made a lot of money. His name was never in the paper. He’s not the finest character that ever lived. But he’s a human being, and a terrible thing is happening to him. So attention must be paid. He’s not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog. Attention, attention must be finally paid to such a person.”

Don’t neglect the working class, Miller says through Linda. Yet that’s precisely what we did under decades of Republican and Democratic administrations since FDR (and local industries spurred by World War II) rescued capitalism from the Great Depression. And here we are. Our working class is furious, and almost as lost as the middle class, trying to make sense of the insensible: why hard, honorable work, work in hospitals and schools, in senior assistance centers, in orchards and restaurants, pays less than moving money around, and grift. Trying, with no cause, to find pride in the art of climbing a greased pole.

In Willy’s mind, there’s a kind of halo around his late brother Ben (Paul Ganus) that foreshadows the MAGA movement’s emulation of its leader. “When I was 17, I walked into the jungle, and when I was 21 I walked out. And by God I was rich.” He found a diamond mine. And that, to the Loman men, is the embodiment of success: wealth in the absence of labor or of contribution. To be fair, Linda finds the prospect, and her brother-in-law’s prospecting, distasteful, particularly after he knocks young Biff down during a playful boxing match. “Never fight fair with a stranger, boy; you’ll never get out of the jungle that way.”

Mark Blanchard stages a fitfully successful production at the Colony. As Willy, Joe Cortese is at least 15 years older than his character, so that he and Fisher’s Linda (who appears to be around 70) strike an impression of grandparents to their sons, rather than parents. In and of itself, this could be a novel approach, rendering Willy Loman as a kind of King Lear. It almost works, except for Cortese’s sometimes mumbling, halting readings. This could be interpreted as Willy’s onset of dementia, entirely justified in the script, except King Lear, too, loses steam without sufficient bombast and confidence. To go high concept for moment, it’s almost as though Cortese’s Willy is a kind of Joe Biden after his one debate with Donald Trump in 2024: He’s fighting to prove he’s still got it, and in moments, he does. But there’s also this nagging sense that he’s fading, and that his company’s reluctance to keep him employed is justified. Not sure this was Miller’s point.

Much of this throws the production’s focus onto the very capable performances by Cullen and Smythe as, respectively, Biff and Happy, and on the second of two-plays within one: the story of a prodigal son who, at long last, at the age of 34, comes to understand, face, and make peace with who he is. When Cullen’s Biff confronts Cortese’s Willy near play’s end, the thunder of the confrontation comes rolling off the stage, from both actors, in a heart-wrenching scene.

Also fine are Hudson’s neighbor Charlie and Oldsberg’s Miss Forsythe (the woman in the restaurant), as well as Chris Ufland’s Howard Wagner, the distracted company boss trying to evade Willy’s pleading to work closer to home. Fisher’s Linda is stoic and sensible, as in she makes emotional sense.

There are other performances where mugging overshadows the sobriety of Miller’s play. Humor and farce are two very different qualities, and there are moments here when the latter takes over.

For all the production’s imperfections, the play comes through. Its glimmers of humor landed with the audience on the night I attended, as did the bursts of recognition that this 75-year-old play is speaking, louder than ever, to our times.

When I was growing up, the legend of the American Dream was contrasted against all those European monarchies with their rigid class system, and it was true. My parents emigrated to California from the UK in 1963. Both were high school dropouts. They each attended the city college and/or state university systems in California. My father became a speech pathologist for the L.A. County school system, while my mother received a PhD from USC (and a post doctorate funded by a federal grant). She taught for decades as a full professor at both Pomona College and Cal State, L.A.

The legend was that the U.S. is a place where every person has an equal opportunity to break free financially, compared to their parents, and rise above them. And if they didn’t succeed, that was on them. In 2025, that blame is sadistic. According to the World Economic Forum, as of 2020, the United States ranked 26th among 82 industrial nations for social mobility. In fact, by metrics of health, education access, education quality and equity, lifelong learning, technology access, work opportunities, fair wage distribution, working conditions, social protection and inclusive institutions, the United States is surpassed by Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Austria, Luxembourg, Germany, France, Slovenia, Canada, Japan, Australia, Malta, Ireland, Czech Republic, Singapore, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Estonia, Portugal, South Korea and Lithuania.

Either he was prophetic or had a bout of lucky intuition, but 75 years ago, Arthur Miller saw this coming. He took a lot of heat for it, because it wasn’t as obvious or even as true in 1949 as it is now — now that the levers of power, corruption and servility have been laid bare.

Panic! Productions, The Colony Theater, 555 N. Third St., Burbank. Opens Thurs., Jan. 16; Tues.-Sat., 7:30 pm, Sat., 3 pm, Sun., 3:30 pm; thru Jan. 26. https://www.onstage411.com/newsite/show/play_info.asp?show_id=7174