America’s Post-Civil War Period Comes Home

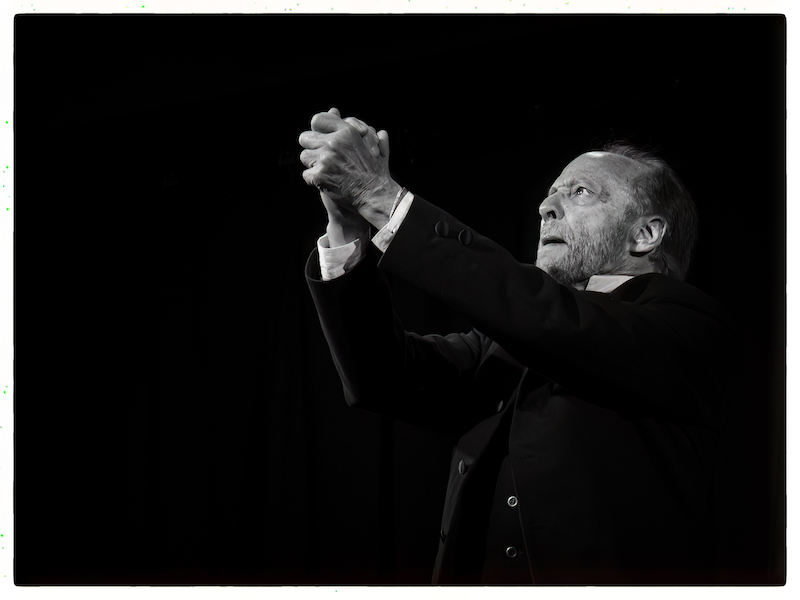

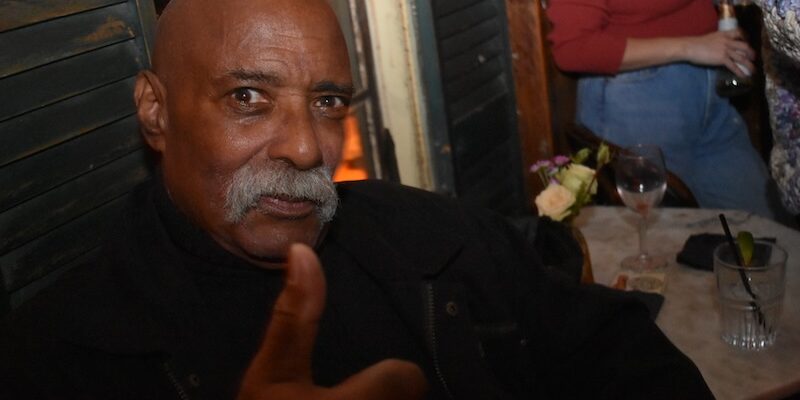

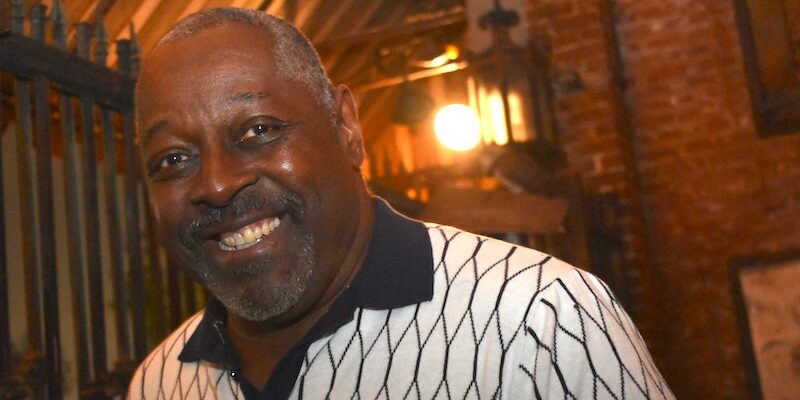

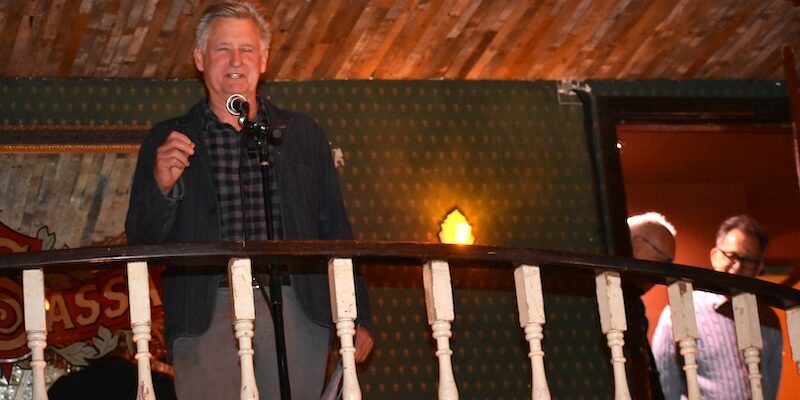

Robert Bailey on his solo performance, “In Some Dark Valley”

By Isadora Swann

Robert Bailey’s solo performance In Some Dark Valley follows Reverend James Brand on a moonlit night. This character, loosely based on Ibsen’s verse tragedy Brand, is a fiery post Civil War circuit preacher who emerges from the shadowy mountains of Appalachia to weave a tale of religious fervor set against a landscape scarred by war, poverty, and disease.

Bailey has been performing his play in festivals up and down California. It plays through March 9 at Pacific Resident Theatre in Venice

STAGE RAW I get the sense that Reverend Brand’s world is filled with trauma?

ROBERT BAILEY Well, this is the post-Civil War period in the South. It’s a defeated place, a defeated land, destroyed really. There’s sickness, there’s poverty, I think about 1/3 of the male population of the South died in the war. So it’s massive. And this is a person whose only literature was the Bible. And so he goes about his preaching … and his domestic life … in a very severe way. There’s one narrow way to get to eternity, and everything else is wrong. It’s only in the very final moments of the piece (it’s 65 minutes long) where there’s some sort of revelation to him about a different way he could have gone about it.

SR: It seems to me that there are parallels between his struggle to see outside of his own perspective and the struggles that America is facing in trying to cross divides of all kinds. Is that part of the reason why you decided to do this piece now?

RB: The simple answer is yes. What started me on this path was a fascination many, many years ago with the original field recordings made by Alan Lomax and others. White and Black Southerners singing. These are people who, for generations, have depended on their faith and expressed it through song. The hard times they went through are real, they’re very, very real, and they’ve continued throughout the 20th century and into this century, right? I had read a headline from USA Today, way back in 2015, “U.S.Torn on Confederate Flag.” And as a Southerner, I’m looking at that, I’m thinking, ‘Torn in what way? . . . What are you talking about? . . . ‘What’s the problem?’ The Confederate flag is what it represents; the South trying to divorce itself from the North to keep its slave population. Everything that started happening around 2020 [re-ennobling the Confederacy] was puzzling to me, disturbing, and as a Southerner, embarrassing.

So I wanted to confront it in some way. And when I settled on the narrative of a preacher, I found an archetype that represents a certain way of thinking. ‘We’re right, you’re wrong’. ‘This is the right way’. And yes, I think that’s one of the roots that’s bugging us right now. I don’t pretend that anything I’m doing captures all of it. It’s just one of the roots, right? And I wanted to embody that and confront it in some way.

SR: You include folk music in your performance. What role do you feel music has in creating culture and in perpetuating it?

RB: Oh, gosh, I mean, the more I study it, it is the culture. It is what makes people unique. If you hear Bulgarian women’s choirs, you don’t hear that music anywhere else in the world. It’s their culture. It’s an expression of their cultural identity. Because of mass culture, and the homogeneity of what gets played, this stuff is going to disappear.

It’s kind of like when you read about languages, you know, primitive languages that just disappear because nobody speaks them anymore. Scientists have noticed that, you know, millions of species are disappearing, right? They’re never going to come back.

These songs, we don’t even know how old some of them are, they passed through so many peoples. They transform themselves over time into variations and then by the time they cross the Atlantic they change again. So, it’s just huge. It is what culture is.

SR: Why is Reverend Brand an important character to embody right now?

RB: Let me step back for a moment. One of my big influences as a young person in college was the Polish Laboratory Theater and its leader, Jerzy Grotowski, who pointed out that it’s very difficult to create pieces that involve myth, or a collective belief system because we don’t have a collective belief system in modern secular society. But what he thought was possible was confrontation with myth. So I was proceeding along the lines of, this character, [this fervent preacher],should be confronted, but in order to confront him, I have to embody him.

That meant dialect, that meant costume. That meant lots and lots of research, lots of books, looking into where this comes from, what the experience of the war in particular was. Both sides prayed to the same Christian God, and both sides evoked that God and the rightness of their cause. The North, after suffering huge losses . . . everybody suffered huge, huge losses on both sides . . . the North was able to say, ‘Well, we were right, God was on our side’. The South had to twist that pretzel in some other way, right? ‘What is God doing to us? . . . Is God testing us?’ It’s a pretzel, isn’t it? It’s a moral pretzel.

I have to tell you that, growing up in Richmond, Virginia, I was not an enlightened person. Very few people around me were enlightened. The attitudes were baked in and we didn’t even think about them. They just were what they were. I was fortunate in that my father, for whatever reasons, when I would come home with certain attitudes and certain phrases or certain jokes or whatever it was, would say, ‘I don’t like that’. ‘I don’t want to hear it . . . You’re talking about people’ And I, I have to, I have to confess to you, at the time, as a child, I was thinking, ‘What’s his problem? . . . Everybody’s like this.’ It’s hard when you’re a product of a certain soil, when you’re grown in a certain soil, it’s hard to see it. So I knew that I had to play this character in such a way that I am inside of him.

SR: There’s something so poetic about what you said about needing to embody something to confront it. What do you think we as citizens can learn from the performing arts? Why should I watch it? Why should I care? Why is this relevant?

RB: I think live theater is a way of experience. It’s a mode of experience unlike any other. And again, Grotowski was very clear . . . he just pared it down to a live human being in front of a live audience. There is an immediacy. There’s an immediate encounter between living organisms and if this is borne out in my piece. It is one of the things I’m proudest of.

SR: The world that you describe this preacher’s world seems really similar to the world today. You know, you talk about young people dying, you talk about wars, you talk about poverty, you talk about inequality. It seems like everything has changed so much, but has the world really changed?

RB: I don’t think so. I just think the clothes are different, the styles are different, the machinery gets different, the technology gets different, you know, and the basic human experience remains the same. And obviously, we’re not up against the same reality. We’re not even up against the same realities that Midwesterners and Southerners went through in the 1930s, with the Dust Bowl and the great migration. I mean, we’re removed from those realities right now. Supposedly we have protections in place that would make those things not relevant to us. Supposedly we would not have a civil war in this country, but that’s a big supposedly, lately, right?

SR: What do you think this character would have to say to a young person like me entering into a world in which great migrations, like what you’re describing from the Dust Bowl, may have to happen again in the next 20 to 50 years because of climate change?

RB: I guess I would put it this way, all of us are on earth for a certain amount of time, yes? None of us really knows, individually, how long that is. Is our experience just, you know, follow the rules, get an education, get a good job, get a good salary, raise a family, make sure you have material comforts, and then that you still have material comforts when you’re really old, and you go to the old person’s home, and hope that you have enough money left over. Is that it? Is that it? Or like the great Peggy Lee once sang, “Is that all there is?” Are we on some sort of spiritual journey?

Whether we know it or not, I believe it’s the second. Now, I don’t want to sound like I’m preaching to anybody. It’s bad enough having to play a preacher. But following a creed, following a prophet, real or false, or somewhere in between, looking for answers, coming up against really harsh realities . . . for example, in this piece, there’s the war, there’s poverty, there’s illness, there’s a plague going around. There’s a lot going on to confront. Young people like you today are entering a world where the battle lines are being drawn. You guys have a whole lot to confront right now in the world. You’re tempted by the tendency to follow, to follow some pathway that might be the way, right? . . . And that I think is eternal. So I would say, if I’m doing my job correctly with this piece, no matter what age you are, if you follow the storyline you should be swept up in this one person’s coming to terms with that. I didn’t feel in a position to judge my character, or anybody, for choices made. But that doesn’t mean the choices are good. In the Scripture somewhere, it says, ‘Judge not, lest ye be judged.’ I’m as tempted as anybody to judge right now.

In Some Dark Valley is being performed at Pacific Resident Theatre, 7051/2 Venice Blvd., Venice; Fri.-Sat., 8 p.m.; Sun., 3 pm; thru March 9. https://app.arts-people.com/index.php?show=271452