Hopeless Hope

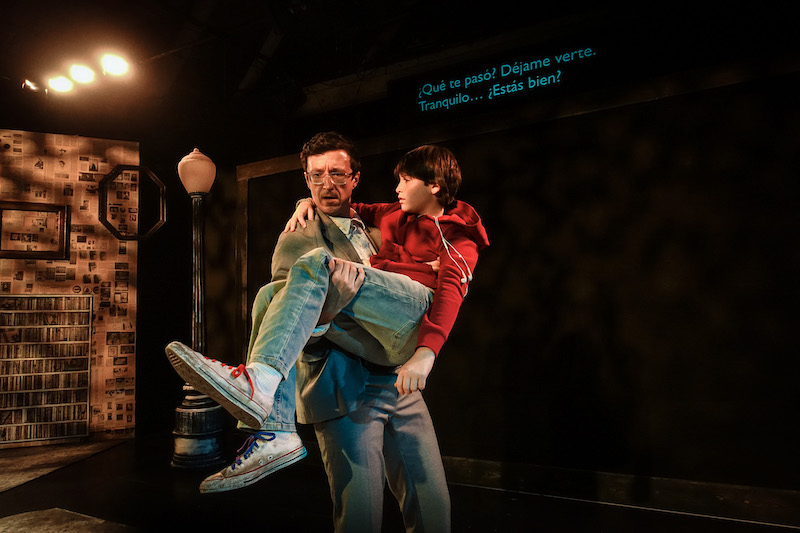

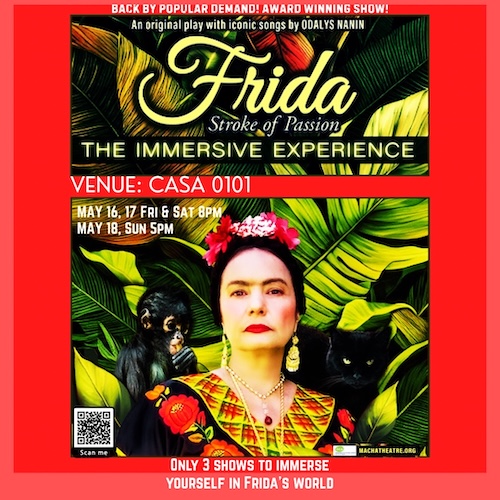

Spy for Spy; Pascal & Julien

The other night on his show, in the wake of yet another New York Times/Siena poll describing the national election as a tossup, Jimmy Kimmel quipped about the lunacy of election polls: their dubious methodologies, their dubious weightings, the number of voters they’re not accounting for (such as the newly arrived youth vote, potentially in the tens of thousands, a bloc that was indifferent until activated by Taylor Swift’s recent endorsement of Kamala Harris). Not to mention how various highly rated polls contradict each other. Kimmel laughed out loud, proclaiming that polls are useless, before admitting to following each new poll with the intensity of an addict, with all the hopeless hope that it might offer a road map.

The other night on his show, in the wake of yet another New York Times/Siena poll describing the national election as a tossup, Jimmy Kimmel quipped about the lunacy of election polls: their dubious methodologies, their dubious weightings, the number of voters they’re not accounting for (such as the newly arrived youth vote, potentially in the tens of thousands, a bloc that was indifferent until activated by Taylor Swift’s recent endorsement of Kamala Harris). Not to mention how various highly rated polls contradict each other. Kimmel laughed out loud, proclaiming that polls are useless, before admitting to following each new poll with the intensity of an addict, with all the hopeless hope that it might offer a road map.

There is no road map. I don’t know about you, but, with a few notable exceptions of some fine reporting, I no longer find even the New York Times to be a reliable source. Its clickbait motives are now glaring, along with the insularity, vanity, and hubris of its columnists plugging their latest books. All of this leads to a superseding, once held and now evaporating fidelity to the truth, swapped out for a fidelity to attention. I gave up on the Washington Post about five years ago, for the same reason. How many articles do we have to endure, leading with “What [fill in the blank] might mean for the future of [fill in the blank]. Or “How [fill in the blank] might blow back on [fill in the blank]. Perhaps some editor on Eighth Avenue believes that these kinds of speculative stories offer insight. They don’t.

So what’s left for those of us trying to fathom what in hell is going on? Twitter feeds? YouTube? TikTok and IG? I found veteran pol James Carville on YouTube today, opining that he has no idea how any of this (the election) is all going to turn out. At least that’s truthful. To say, “I don’t know” or “I just have a feeling” [that Harris won’t lose this election, as he later told Anderson Cooper] maybe the most honest claim one can make in this terrifying, venal era of perpetual distraction.

This current cultural moment harkens back to thoughts expressed by Kurt Vonnegut (the 20th century’s Mark Twain and author of Slaughterhouse Five, Cat’s Cradle and Mother Night, among other novels and stories) and provides a lens through which to view a pair of plays in local stages: Spy for Spy at the Whitefire Theatre, and Pascal & Julien at 24th Street Theatre.

Kurt Vonnegut, Tribal Storytelling and Shakespeare

As a young man, Vonnegut served in the U.S. Army during World War II. He was captured in the Battle of the Bulge by the Germans and held as an American Prisoner of War in a Dresden labor camp, manufacturing vitamins. This experience helped forge his central character, Billy Pilgrim, in Slaughterhouse Five (Vonnegut was held by the Germans in a former slaughterhouse). Billy Pilgrim is a bewildered young man being held prisoner in Nazi Germany and trying to fathom what it means to be an American in such circumstances. In a 1987 interview, Vonnegut noted (27 years ago!) that the United States was ripe for fascism. “If we treat each other this badly, in a time of prosperity, on borrowed money, how are we going to treat each other when the real trouble comes?” he asked rhetorically.

Naive and idealistic, Billy Pilgrim can’t quite understand what is happening around him. Truth being beyond our grasp is among Vonnegut’s fallback positions, in literature as in life.

In 2004, Vonnegut delivered a lecture at Case Western University about the shape of stories, what shapes are artificial and what shapes reflect core truths. He briefly studied cultural anthropology, he said, until he realized, “I hate primitive people; they’re so stupid” (a completely sardonic, sarcastic remark).

In the same self-mocking tone, he ridiculed their story telling: “‘We came to a river, a little beaver died.’ You can’t tell what the good news is and what the bad news is!”

This is contrary to commercial Hollywood storytelling, with its action rising and falling, where good triumphs over evil and you know exactly what is good and what is evil. “This rising and falling is artificial,” Vonnegut added. “It pretends that we know more than we actually do.”

He then turned to Hamlet, in which a young, depressed student sees the ghost of his father, the late Danish king, who tells him to avenge his murder at the hand of his brother, who has now stolen his throne and his wife. Uhm, that’s a ghost telling him this, right? Hamlet doesn’t know what to believe, and neither do we. This could all be a cosmic trick, the devil’s design. This could be the conjuring of spirits, disinformation being spread by Iran or Pakistan or Russia, to lure him into the underworld. The action gets rolling when Hamlet accidentallykills his girlfriend’s meddling dad, leading to a cycle of revenge — all triggered by this one screwup — leading to the deaths of almost everybody in the play, diabolically and absurdly. Is this good news? Is this bad news? Who’s to know? Pointlessly brutal stuff just keeps happening. History. We come to a river and a little beaver dies. Vonnegut cycles back to the parallels between the ancient tribal storytellers and Shakespeare, and their mutual brilliance.

Said Vonnegut, “Shakespeare tells us we don’t know enough about life to know what the good news is and what the bad news is, and we respond to that. . . We are so seldom told the truth, and Shakespeare tells us the truth.”

Spy for Spy; Pascal & Julien

Kieron Barry, an ex-pat Englishman, wrote Spy for Spy for two actors, closing its run Oct. 10 at the Whitefire Theatre in Studio City. Daniel Keene, an Australian, penned Pascal & Julien, another two-hander, very short (45 minutes) and being produced and presented by the 24th Street Theatre through October.

Both are what I’d call microscopic, relationship plays, beautifully staged and performed. Pascal is completely linear — a sequence of sketches between a boy, Julien (Darby Winn, sharing the role with Jude Schwartz) and a man, Pascal (Paul Turbiak). They are strangers at first, and the play follows their awkward, sometimes bumbling friendship after they first meet at a cafe in Paris, where the play is set.

Julien has an emotionally absent (offstage) father, and for a reason that I couldn’t quite fathom, chooses an adult stranger, Pascal, sitting at a cafe trying to concentrate on a crossword puzzle, to fill in as his dad. At first, the man completely disregards him, tries to get him leave, but the child is precocious, even relentless, as though the man’s clinical disinterest is what the boy finds so interesting. This is odd, but it’s also life, where we can’t tell what the good news is, and what the bad news is.

In one scene Julien claims they like each other because they’re both annoying, which is true. Having two annoying characters populate a play is not necessarily bad storytelling, however. It takes our minds away from the insipid, oft-held mirage that characters must be sympathetic to be stage-worthy. Rather, it concentrates our focus on the ache in both of their souls, the loneliness of our times, the kind of loneliness written by the likes of William Inge and Tennessee Williams in the prior century but which now seems accelerated by social media technologies and algorithms that purport to bring us together while, in many ways, doing just the opposite. Just check the suicide rates among teens and among seniors, and how they’ve skyrocketed since the mid-20th century.

There’s this child, leaning in for love. And this man, self-possessed, self-absorbed, self-satisfied, doing just the same. Symbiosis.

And so they start to hang out together, at various locales: the cafe, the park, the riverbank. This growing friendship had me clutching the side of my chair hoping this wouldn’t start to get pervy. It didn’t, largely because of Turbiak’s facade of disdain as Pascal.

Buried deep within that disdain is a seed of vulnerability, what might be called a hopeless hope for connection, for a friendship as innocent and child-like as the child himself. And that is the point — that the two are mirrors of each other, engaged in a slow dance of role reversal. No good news. No bad news. Just something small, representing something much larger, unfolding.

The theater was filled with young people at the performance I attended, and this story’s connection to them was evident. Credit must also be given to Debbie Devine’s taught, tender staging, to Keith Mitchell’s spare, efficient stage design, accented by Matthew Hill’s video design. The videos employed the labor-intensive rotoscoping technique, taking photographic images and, frame by frame, transforming them into animation, used in scene transitions to help smoothen the story’s many truncated scenes.

Meeghan Holaway and Andrea Flowers are the two actors appearing in Barry’s Spy for Spy. The playwright told me that he’d written the play with Holaway in mind, and after seeing her droll, finely nuanced performance, that makes good sense. Holaway did not appear in an earlier production of the play in London, however, where it was well received.

For the small cluster of audiences that follow local stage productions, one of the delights is seeing our best actors pop up across town in various productions. Such is the case with Holaway and Flowers, who appeared together in Steve Yockey’s Mercury at the Road Theatre Company earlier this year.

Spy for Spy is like a variation on Pascal & Julien, though the two plays were written continents apart. In this case, two women, strangers to each other, meet at a Napa Valley wine-tasting event, and in a series of scenes, engage in a romance that ultimately deepens over years. Whereas in Pascal, the “adult in the room” comes dressed in a coat of emotional armor, Spy‘s elder partner Sarah (Holaway) sheds that coat in two blinks. She puts on airs of maturity, which we see melt into emotional desperation and dependency. Meanwhile, young waif Molly (Flowers), working as a wine server in that Napa establishment, plays it as an open book — both the character and the actor. This open book is a dumb one (she doesn’t know, for instance, that north and south are fixed directions rather than personal interpretations), until she reveals a level of emotional and even spiritual perceptiveness that leaves Sarah in the dust. Molly’s mercurial personality may well be the source of Sarah’s attraction to her.

In this way, both plays traffic in the art of decoding. All the characters, and audiences, are simply trying to fathom what in hell is going on. And both plays are located in hell, engulfed not in flames but in that overarching isolation that feels so emblematic of our times.

Once again, there is no good news, no bad news, just a series of events through which four characters in two plays are trying to decode words and tone and cadence and body language, and to excavate the hidden truths of their respective partners. Because, as in our current political discourse, the words alone are next to meaningless, just tools of a strategy to win the current argument, or power struggle, or election. When Sarah makes a bold statement at the start of the play, by story’s end, she’ll prove just the opposite. The same is true of Pascal. Words are mere instruments for the moment. The truth is something different entirely, and it’s unfathomable to mere mortals.

Among the many joys in Spy for Spy is Barry’s razor sharp repartee, in conjunction with Holaway’s often flummoxed, aghast and sometimes dryly sarcastic responses to Molly’s free-wheeling though sometimes prescient logic.

Before the start of the play, the audience chooses the sequence of scenes (to which the actors gamely adapt), though the first and last scenes are fixed. Having the audience determine the structure by voting is gimmicky, but the result is profound, at least if the scenes defy linear sequence, as they did for the performance I attended. This means we’re watching characters respond to events that they’ve lived but we haven’t yet seen, but will soon. This completely upends traditional dramaturgy, so that the story unfolds as it would in memory, in bursts. We’re compelled to put together the story ourselves rather than having it served up in some Napa Valley wine-tasting cellar. All of this underscores a lyric in an old Harry Nilsson song, “Life is never what it seems, dream.”

In this way, Spy for Spy is both microscopic and cosmic.

Michael Massey’s staging is as meticulous as it is efficient, and he must share in the credit for this pair of glorious performances.

PASCAL & JULIEN Produced and presented by 24th Street Theatre, 1117 West 24th Street, LA; Sat.-Sun., 3 pm, Sat., 7:30 pm; thru Oct. 27. www.24thstreet.org

SPY FOR SPY The Whitefire Theatre, 13500 Ventura Blvd., Sherman Oaks. Thurs., 8 pm, thru Oct 10; check website for alternate locations in Ventura and Santa Barbara. https://www.ticketleap.events/tickets/spyforspy/shermanoaks