Atwater Village Development Project

Why Gates McFadden Runs a Small Theater Next to the Train Tracks

BY DEBORAH KLUGMAN

Gates McFadden is the artistic director of Ensemble Studio Theatre/L.A. In 2011 McFadden directed House of Gold by Gregory Moss, which was inspired by the JonBenét Ramsey tragedy and reflects on the phenomenon of child beauty pageants and its pernicious impact on unknowing and acquiescent children.

McFadden is currently developing a play about Cuba by Vancouver-based Timothy Perez, one of her former students she met while teaching at Tisch School of the Arts. McFadden directed a workshop presentation of Perez’ play last week at her own theater.

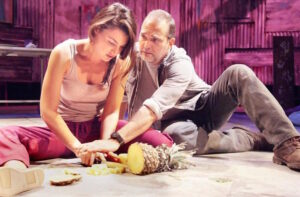

She also directed the company’s recent, highly acclaimed production of The Ugly One by German playwright Marius Von Mayenburg, (There are uncertain but hopeful plans for a future mounting). It’s a dark, funny, disturbing tale about a brilliant inventor who, midlife, learns that his boss refuses to let him represent his own invention at a convention, because he is regarded as ugly by everyone around him – something he never before realized. When he undergoes cosmetic surgery and acquires a stunningly handsome new face, he becomes universally admired – until others undergo the same procedure and he devolves into one among many.

STAGE RAW: What first hit you about The Ugly One?

GATES McFADDEN: What first hit me was the concept of trying to be so special. I think it was one of the last lines. “Stop trying to be so different.” It was an interesting thing because I [found myself thinking]: Oh, I want to be seen as special. How do I do that? Am I trying to be special by having fewer wrinkles than the next person, or because I’m trying to do this really interesting work? Is it a mixture of a lot of things? . . . I feel that there is a huge amount of narcissism [in our culture]. I am certainly involved in it . . . Falling in love with [myself.] That’s why the play was very funny to me and very frightening, and viciously cruel.

It’s not vicious for the sake of being vicious. It’s like: This is how we hurt each other all the time and we’re not even aware of it. We say things that deeply wound people. We want them to change and be our image of who we want them to be.”

What about your relationship as director to the audience?

I like the discovery of what the audience brings. I remember when I was doing Cloud Nine [Caryl Churchill’s play bifurcated into an act set in Victorian England, and another Act set in 1979 London] about and I was getting a great audience response and then someone said, can’t remember who: “No, no, it’s becoming too sentimental. Pull back.” And they were right – because I needed to let [the audience] respond, and by my responding too much I was telling them what to do and I do not like that. I do not like indicating. I do not like all that stuff. You can get up on the stage and pick your nose and get a laugh. It’s not hard. Or you can do something and get people to cry. It’s about what you are trying to say. What is the event? What’s going on here? What do we want the audience to take away? And I like to set a fairly high standard of having people keep the experience in their mind, even if they hated the experience – to at least think about why they did. Because I’m going to be thinking: Why did they hate it? Or what did they love about it? That’s kind of why you do it.

People saw House of Gold, and found it such hard material . . .

This is Gregory Moss’ play about children and sexual abuse?

Right. No child was harmed because [the child] was played by an adult actor. On the other hand there was all this intensity because people would project and imagine what was going on. And that’s one of the things that I was actually exploring with the audience: How voyeuristic are we as a public? We don’t like [exploiting/abusing children] but then there’s a part of us that wants to see it. And some people use that [voyeurism] to bad effect. With all the technology there is sometimes a loss of innocence.

I remember that I was very taken with it but the person I went with was totally freaked out about it: “I don’t like this play. I don’t want to be here. I don’t know why they are dealing with it.”

About three years ago, there was this “Honey Boo Boo” [pageant shows with kids] on TV. I couldn’t believe how many people were watching it, going “Oh yeah it’s horrible, it shouldn’t be happening”. But no one was saying you can’t put that on TV. The attitude was, it’s fine if the parents want to do that.

When a kid is that age and a minor, of course they’re going to want to please their parents. It’s where this whole cycle starts that ends up with The Ugly One. Is it about the talent or is it about all the accoutrements? If you’ve gotten to the Olympics you know it’s because of your skill. But if you win a beauty pageant I’m not sure what that means.

You don’t have to do anything for people to think you are beautiful. If you’re an athlete you have to prove something, or if you are a writer – but if you are considered beautiful all you have to do is stand there.

Right, except then what starts to happen? And this is why I thought The Ugly One was so great: What if you could make yourself to be that beautiful? What if it’s something like a commodity that everyone can buy? And then it doesn’t become so special. And then, who’s face is it? If the surgeon makes it, is it yours? What if that face is everywhere else? I think that’s funny and interesting, because you go on the Internet and you see how many products there are about how to become more beautiful.

But it’s more than that. It’s how people see you. If you’re told [you have] the most beautiful face, how people react to you will start to change you. How can we maintain our identity and be ourselves, and old, and not look like 16? How does it affect us if we think we’re ugly? How does it affect us if we have no idea that we’re ugly, which is the way the play starts. It’s not like [the lead character] has been living with this burden. He has not noticed that even his own wife is not looking at him with both eyes.

Would you say you are visual in your approach to your projects?

I use a lot of images. I think in movement and rhythm. I am definitely very visually oriented when I direct. I am a big collector of old magazines and art books. I love film, I love opera, I love all of the arts. It comes from my background.

Which is?

Very early I got to study with Jacques Lecoq. From him I got the notion that as an actor you have a responsibility to work with other artists. You work with musicians. You work with architects. We had a whole thing about architecture with Lecoq. For example, what’s the relationship of the performer in that space? What’s the relationship of the set in that space? Is it an environment? What’s the relationship between the spectator and the performer?[In the theater], anything can go wrong. And in one performance [of The Ugly One], somebody passed out. We didn’t know if it was serious or not. We had to stop the performance.

How long is the rehearsal process usually?

This one was very short and so it was intense. It was hard on the actors. I was quite a taskmaster. We only had four weeks and then we were into tech, and tech was complicated. But the plus was, it was not a three-hour show. It felt like more sometimes because it’s so dense but actually it was only an hour and five minutes, so that’s a short process.

What are some of the difficulties of your job as artistic director?

One frustrating thing in a non-profit theater when you are as small as we are is that you have these incredible artists and writers but there’s no money for anyone. And so you can’t get people to commit to a rehearsal process the way I would like to do. You can’t have those rehearsals of eight-hours for six-months because you’re a company and you’re developing it. And I do feel the best work comes out of that particular process. The theater that I love the most comes from companies that have grants that allow them to work on something and redo it. That would be my ideal. And from my short experience as an artistic director, I can’t do that. That’s been very frustrating for me. I wish there was some way that I could have a magic wand and I could work on something, and then, when it’s ready, open it.

What about casting? Do you cast from within the company?

Our productions are always at least 50% from the company, if not all. We have another play coming up. It’s a beautiful story written by Stephen Dierkes. He is in our playwright’s unit. It’s a simple story, it’s beautiful.

Are you directing it?

I’m not going to direct. I’m going to give other people a chance.

I know you have a play-reading series but do you also have a writers’ workshop where people give feedback.

Yes, we have that, and we have several playwrights who have their own playwrights’ group. Our own playwrights unit, headed up by Tom Baum, does meet and they do give each other feedback.

What about marketing?

I’m certainly not an expert in that field. Sometimes you can have a gem that’s been done and nobody told anyone how brilliant it is and it’s one night only. You can just go to a reading and if it’s done well you can have a cathartic experience, depending on the subject matter.

Other projects in the works?

There was a three-minute sci-fi writing contest – short story — a page and a half of writing. How much can you tell in three minutes. It’s to be done on the radio, and I’m going to direct some of our actors. We just got them, the three winners. Apparently they have just hundreds of these from all over the country. You can get a lot in, in three minutes. My mind just kept going after the end line.

I love that. Where I’m taken. I mean, that’s why we have the arts. I can be taken by a painting. I can be taken by a good piece of pie. The idea – where you are so engaged in something and it’s opening up this whole other experience. And that’s really why you do it, isn’t it?