MORE FRINGE REVIEWS HERE, HERE, HERE, HERE, AND HERE

Notes from Arden

Fringe Cruisin’

By Steven Leigh Morris

What a strange hot-ice mix of self-promotion and community our Hollywood Fringe brings to the fore. As Paul Birchall points out in his second Letters From the Fringe column, the roll-call of thespians troupes, many in costume, gathering on Lillian Way to load in their props and sets for their one-hour shows at Theatre Asylum looks like a series of costume parties. Trucks come and go. Companies promote their own shows, as they must, and then move on. It’s laizzes-faire. Everybody’s doing their thing, within the well-managed tech and safety constraints of Fringe management – i.e. be in on time, out on time, find your space, pay whatever rent the market will bear, and hope your audience expands beyond your circle of family and friends.

Casual observation suggests audience growth is happening. On bicycling up and down Santa Monica Boulevard this year during the Fringe, a common sight outside the Complex and Elephant theatre complexes was crowds gathered outside the theaters, and the kind of foot traffic down the Boulevard between Cahuenga and La Brea seldom seen outside June. After watching a dozen shows selected randomly this year, it was clear that the average audience was up to between 50-70 per cent of each venue’s capacity. In the Fringe’s first year, five years ago, most venues of 50 seats averaged audiences of about 10 people. What accounts for this uptick? Who are these audiences? Other participants, who have finally relaxed sufficiently to open their hearts to other people’s work? (I kept running into actors who were now Hollywood Fringe veterans, returning to perform year-after-year.) Has our Fringe attracted a consortium of non-participant fans enjoying the risk and reward of our completely un-curated, largely democratic come-one-come-all popularity contest? If anyone can get some hard data on who the audiences are, that will go a long way to explain what this robustly evolving event is really about.

As for the shows themselves, those that shone brightest tended to be those with a history, i.e. Beth Dies’ production of Chiara Atik’s Women, already established in New York.

Women (Theatre Asylum) is a stylishly-directed (by Stephanie Ward) spin on Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and features a quartet of sisters (Layla Khoshnoudi, Abby Rosebock, Rachel Lin and Lydian Blossom) who, though in early 19th century attire, speak with 21st century lingo and show wry, sarcastic facial expressions that describe today’s teens. Their mom (Vicki Rodriguez) and the men in their lives (Zac Moon, Bradley Anderson, Stephen Stout and Brett Epstein) express themselves in 19th century cadences, suggesting that the plight of the mod femme quartet, as they live and die through childhood and young adulthood, is very much tied to pressures that have been around a while. Women goes one baby step further than Theatre Impro’s (the excellent L.A.-based improv troupe) gentle riffs on various styles of classic lit. Women is a scripted satire of the present informed by the past, contrasted against Theatre Impro’s loving, improvised send-ups of what went before.

Over at Three Clubs on Vine Street, Chris Farah’s solo show Fancy: Secrets From my Bootydoir (directed by Kurt Koehler) hails from Silver Lake’s Cavern Club and is a wildly entertaining piffle, featuring a character who’s part Jackie Beat and part Divine – a chanteuse and formerly white-trash waif who found prostitution as the key to her queendom. She now gives sex advice to people who text in questions during the show. In a wig recalling Tammy Faye Bakker, Fancy Jean Baker is a charismatic cartoon with a history, a woman with a male libido and female compassion, she’s Dear Abby on Viagra, with some Red Bull thrown in for an energy boost.

Thomas Christensen is Danish, which might explains his glee at making fun of Germans. Christensen does a bang-up job impersonating fictitious German life coach Jurgen Liebedich in his solo show The Divine Teat (Theatre Asylum), in which, like Fancy Jean Baker, he lives to give satire-drenched advice. The pinnacle of his act consists of large yellow balloons, representing breasts, which he bounces into the audience, encouraging us inmates to suck on the nipple, to derive a problem-solving force from the divine entity that Liebedich has built his career on defining so badly. The show is a delight built on platitudes, and the wry dismantling of them. Still, the joke is ultimately obvious. There’s a surprise in there somewhere, waiting to be unearthed. That’s when Christensen will have a show that digs slightly deeper. That probing would be worth the effort.

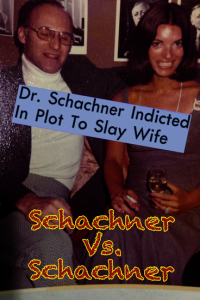

Another top-tier show defies the pattern of strong performances having a history. Abbie Schachner’s one-woman show Schachner Vs. Schachner (Theatre Asylum) is a world premiere. It also defies the warning against using literal autobiography as the foundation for performance. There are two sets of parallel combatants in Schachner’s quasi courtroom drama (preserved in newspaper clippings), in which she sifts through the charges filed against her father that he hired an assassin to off her mother during a divorce that redefines the word acrimony. Abbie was an infant during all this, and now she’s trying to put the pieces together – is it possible her dad was set up? One set of combatants is obviously her parents, the other is her heart and her soul, trying to reconcile this sordid episode of family history. Abbie is a vivacious and personable performer – she was dropping lines and losing composure during the preview I saw. Even so, as a work very much in progress, this is a fascinating saga that speaks to the dubious nature of empirical evidence and the depths of hatred that can foment within marriage. And then there’s the comedy: “Is it true you left $11,000 in the glove compartment [for the assassin],” she asks her father. “That’s not true!” he replies, indignant at the libel. “It was only $10,000.”

Also ripped from the headlines is John Hendel’s W.E.A.R.H.O.R.S.E. (Theatre Asylum) based on the TV-news account of a woman who slithered naked and bloodied within the carcass of a slaughtered horse. Erica Bradley and Brendan Bloom portray, respectively, the woman, a performance artist, and her boyfriend, resentful of the attention she’s getting and eager to leave his own mark on the world via an art project. He’s also the one who shot the “haas” (he’s incapable of pronouncing the word “horse” – a running joke), and his self-respect is tethered to his ability to prepare a horse-meat dinner for his girlfriend and her contemptuous (of him) mother (Angela Leib). Under Ruth Du’s direction, the cloth horse mingles with liquid blood – a metaphor for how the jokey, insular world of performance eventually meets TV-news realism, yet the play’s world is too idiosyncratic to be much more than a curiosity.

Celia Dufournet’s solo slice of agitprop physical theater, Food Empire (Schkapf) aims to bring the whole world onto the performer’s shoulders. In a lacy skull cap, and frilly dance wear, she executes balletic contortions around a Food For Less shopping cart, which for a moment becomes her prison. There’s also a rope which she places on the stage floor into the general shape of the continental United States, and hundreds of bullet casings which she deposits within the rope’s perimeter. The audience is invited, shall we say goaded, to help shape these casings into designs of its own making. We are also asked to provide sound effects for Dufournet’s climactic scene, then we’re chastised for our lack of enthusiasm in doing so. Given that the audience contained four people on the preview I attended (that includes the former FDA official who bounced up after the show for an unannounced lecture on government-corporate malevolence leading to the toxic profits from fast food), the crowd’s reticence was understandable. The underlying truths in Dufournet’s compilation of texts about the evils of the way food is processed in our culture are unarguable. Alas, the show tries to pass off its rectitude for wisdom, and that’s a dangerous strategy in the theater.

Fabulous Dreams productions rolled into town from Italy for its production of playwright-director Fabio Zito’s The Perfect Lover (L’amante perfetto) at Theatre Asylum – which resembles a 1950s Italian comedy about a man (Ricki Tursi) in shock after discovering the attraction between his wife (Patricia Campanile) and his mistress (Vanina Arias), and their ever-so-grown-up agreement to share him, and each other, sexually. (That’ll show him!) It’s what the British would call “dodgy feminism,” performed in Italian-accented English by the charming ensemble. Even so, Tursi’s expressions of comically hypocritical dismay at his wife’s ability to candidly counter his adultery grow as threadbare as the play itself.

The Best of Craigslist: Live! (Hudson theatres) has actors enact the goofiest ads on the famed website. Despite some nice cameos by Ian Forester and Michael Dunn, the humor inherent in the postings is mostly overblown by the ensemble, vanquishing the comedy that the show intends to accentuate.

I first saw Colin Mitchell’s solo show, Linden Arden Stole the Highlights, based on the Van Morrison song, some 18 years ago, here in L.A., when both Mitchell and I were considerably younger. In the midst of a drinking binge while marooned in a tiny Scottish village, Mitchell’s Arden discovers what may be an audience, or ghosts, perhaps? This is a living dramatization of solipsism, in which we’re mere figments of the central character’s whiskey-soaked imagination. Then again, both Colin Mitchell and Linden Arden of 1996 are both, also, now figments, as are the Mafia in San Francisco whom Arden fled years ago (after pocketing enough cash to get him established in Arklow, Scotland). So the distinctions between what’s real and what’s imagined in Arden’s world are deliberately blurred by director Christian Levatino. A soccer ball that bounces in from the neighborhood kids looks real enough, as do Arden’s explosive rages at those kids. Linden Arden is unhinged. That’s what the toxic blend of isolation and time does.

On the night I attended, the play’s opening rites of Arden shaving and preparing to attend his weekly church service in the town where he has precarious bonds seemed more sluggish than I remember. The Arden of 1996 was a youth, an imp. Sprinkles of silver now adorn his beard. (The age and the gravitas suit the story well.) Still, the story itself, in 2014, didn’t start clicking until the arrival of those ghosts from San Francisco, coming to take Arden “home.” This is where Mitchell’s silver hair added to the poignancy.

But of course, we see Arden’s compatriots only through his story-telling. They’re not a fraction as “real” as that soccer ball. Are they, too, a figment? A legend? Arden’s reaction to them is apocalyptic – the weirdly plausible mystery and wonder being that, in a town with no police, Arden suffers no legal consequences from a spate of (described) violence that he unleashes, perhaps because that violence didn’t actually happen? The purpose of a story is to make something manifest from mere words. The story is stated, but the theme is understated: that the demarcations between the real and the surreal, between a legend, or a song, and the events it derives from, are principally unknowable. The inability to distinguish between dreaming and living, between fiction and non-fiction, is one definition of lunacy. Linden Arden is decidedly at that point.

I described the performance in 1996 as “a testament to the capacities of storytelling,” and I stand behind that, still.