Flight of the Bumblebee

A Life in Our Theater: A Memoir

BY NEAL WEAVER

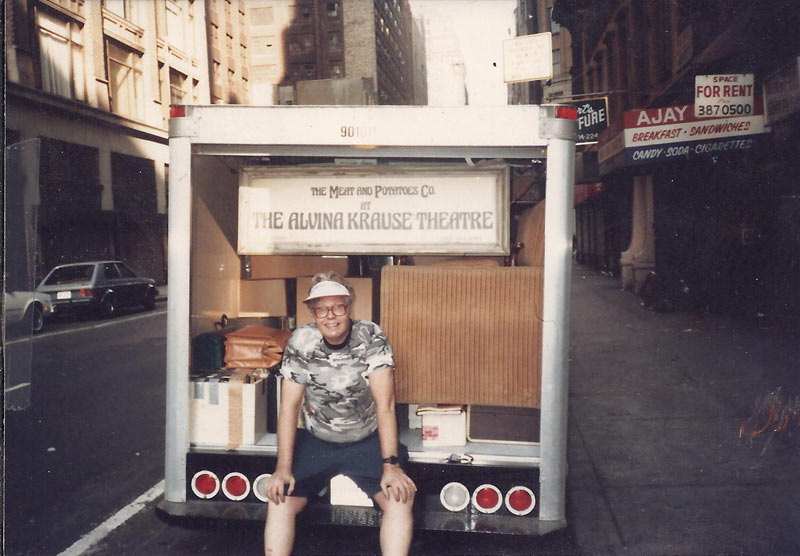

When I relocated from New York City to Los Angeles, in 1987, it was with very mixed feelings. On the one hand, it was exciting to think about moving to a new city and beginning a new life. On the other hand, I was already 52 years old, and trying to start anew at that age was daunting. And beneath all the other feelings lurked a huge sense of loss. I had launched an Off-Off-Broadway company in 1976, and we had mounted some 92 productions in just under 12 years, all of which I had produced, and many of which I also wrote, directed or designed. But things got a bit harder every year, and it was clear that we couldn’t go on much longer.

The situation in 1987 New York was much like Los Angeles in these last couple of years. Real estate prices were soaring, and many 99-seat theaters were going under. In 1976, I’d been able to mount a production for $876. A decade later, costs had risen to $10,000 per show. The actors’ union (Actors’ Equity) kept upping the ante on what we had to pay the actors. Rent had gone from $750 a month to $2,2020. Then we received notice that our rent was about to double, to $4,4040. There was no way we could raise that kind of money, and residential rents had risen with equal speed, partly because of growing gentrification. I had been living in the theater, and current apartment rents made it clear I could no longer afford to live in Manhattan. There seemed to be nothing left for me in New York, and I had friends who had moved to L.A. and were doing very well.

One was a writer for a cable sitcom. He assured me that if I came to California, he could get me a job as a writer on his show. So I rented a small moving van, packed my belongings, and headed out. I had some vague idea of starting another theater company out here, so I packed a choice selection of props, costumes and furniture from my theater.

Photo: Courtesy Neal Weaver

It proved much harder than I expected to reboot my life in Los Angeles. Everything was much more expensive than I anticipated. By the time I’d found an apartment in Hollywood and bought myself a used Ford, my nest egg was nearly gone. Shortly after I arrived, the writers’ strike shut down much of the film and television production. And by the time the strike was settled, the cable sitcom where I’d hoped to work had folded its tents and disappeared. I was left scrambling for a job. I tried to get to know something about theater in L.A., but that too was hard.

As one who’d learned to drive in my small home town in Kentucky, I’d never driven in city traffic. I was terrified of making left turns, and drove around in circles to avoid them. I hadn’t yet learned my way around the city and avoided going anywhere outside the immediate Hollywood area. Theater tickets cost money I couldn’t afford. And since I had no knowledge of individual theaters, or their reputations, I saw a lot of really bad theater.

Venturing out to the smaller theaters (they were cheaper), I was struck by how small they were. I’d been to one theater in New York that had only 16 seats, but that was the exception. I expected 99-seat theaters here to have 99 seats, but most of them were smaller, some with 12 cup coffee-makers for their audiences. At my company in New York, we’d had a 200-cup restaurant urn. Maybe New Yorkers just drank more coffee.

I was also struck by how many productions utilized a nearly bare stage, and that the style of performance tended to be far more presentational than I was used to, with a lot of actors playing directly to the audience rather than to their fellow performers. And I was seeing things that challenged all my basic assumptions: When I discovered that there were theater folk who wanted to totally dispense with psychology in their work, I had to re-evaluate and rethink everything I thought I knew about theater.

I also began to learn a little about the way theaters operated here. The Actors’ Equity rules for 99-seat theaters were far less restrictive here than in New York, where it often seemed that the actors’ union was intent on putting the smaller theaters out of business.

(At one point I discovered that, on the union’s committee that made decisions about New York’s 99-seat theaters, not one member had ever worked in a 99-seat theater and most had never even attended one. There was an old guard that hated Off-Off-Broadway and actively sought to destroy it.)

But there had been advantages in New York as well. It was easier to get around on public transport, and theaters didn’t have to worry about providing parking areas. New York also had something called The Costume Collection, supported by the New York State Arts Council, where a costume could be rented for the run of a show for $15, while in L.A., era-specific costumes had to be rented by the week from commercial costume houses, at prices that struck me as exorbitant. There was also an organization in New York called Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts, which provided pro bono assistance to small theaters. When my theater, The Meat and Potatoes Company, needed to file papers of incorporation, they supplied us with an attorney, Mitchell Pines, who took care of all our legal matters gratis, except for his out-of-pocket expenses. He stuck with us through the years, defending us against a couple of frivolous lawsuits, and bringing his wealthy friends to see our shows. (He once said to me, “Don’t ever feel hesitant about asking the rich for money. They expect to be asked, and will probably be disappointed if they aren’t.”)

L.A. has an organization called California Lawyers for the Arts. When I went there, the initial consultation was free, but after that the lawyer charged hundreds of dollars per hour. (California Lawyers for the Arts still exists and does have a pro bono program, but it requires a special application with specific requirements for arts organizations to qualify.)

I did not keep records of the shows I saw in the first year or so, but I remember that the first was a production of Jerker, Robert Chesley’s drama about phone sex and AIDS, with Michael Kearns, at Smitty’s Fifth Estate Theatre, at 1705 N. Kenmore Avenue, just north of Hollywood Boulevard. Since I didn’t know the neighborhood, and had no idea about parking, I decided to try the city buses for the first time. I had no trouble getting to the theater, but after the show I had to wait forever on a bench at the bus stop. Someone passing in a car shouted at me, “You’ll be sorry!,” which I took to be a comment on the bus service. I waited more than 45 minutes but no bus came, so I started walking west, figuring if a bus came along I could catch it at another stop. I walked almost two miles along Hollywood Boulevard, from Kenmore Ave. to west of La Brea Avenue, and no bus ever came.

I also remember venturing downtown for the first time to see a nice production of Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mr. Sloane at the Mark Taper Forum. A production of Hedda Gabler on one tiny cramped stage offered so little room the actors could hardly move. In a nutty modern-dress production of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, John the Baptist was imprisoned in a telephone booth. The Open Fist Theater was still on La Brea then (between Sunset and Hollywood boulevards), within walking distance of my apartment, and I saw their production of Brecht’s Baal, in which artistic director Martha Demson played a man. And I had my first encounter with Alan Bowne’s Orwellian AIDS-drama Beirut, which I had to sit through far too many times later.

Eventually I saw an ad in a paper called the Village View saying they were looking for reviewers/critics. (Can you imagine today any newspaper advertising for critics?) I applied and got the job. (It would later be called the L.A. View ‘till it was bought by the self-styled libertarian anarchists from a company aptly named New Times, which fired all the reviewers and put a couple of other papers out of existence.) Then, fortunately, I was hired by Steven Leigh Morris to join LA Weekly’s team of critics. Since then I’ve seen hundreds of shows, ‘till the Weekly decided to eliminate most of its reviews.

Now I’m hoping for the best with the websites Stage Raw and Arts in LA. I was never able to launch another company. (When it became clear that starting another theater company, in L.A., was a pipe dream, I contributed my stored costumes to The Actors’ Gang. The furniture and props served to furnish my apartment.) However, I have managed to direct a couple of shows, including one that I wrote and produced, to present some readings and some workshop productions.

What conclusions can I draw after spending almost 60 years working in and around theaters? For one thing, it seems the quality of acting and actor training has improved immeasurably over the years. Certainly it’s disheartening that the print media has reduced its arts coverage to near zero. Those of us who are aware of the richness and breadth of L.A. theater are always disconcerted when some uninformed soul asks us, “Is there theater in L.A.?” Now the outreach is more limited than ever, unless we can educate the general public to the sizeable quantities of information, reviews and debate to be found on the Internet.

Sometimes it seems that we don’t matter to anyone but ourselves. But it’s not for nothing that George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart called the theater The Fabulous Invalid. As Oscar Hammerstein and Richard Rogers observed in a song from their 1953 backstage musical Me and Juliet, the theater is always dying:

The theater is dying,

The theater is dying,

The theater’s a thing of the past . . .

Except that it doesn’t die. It just changes. And as long as writers, performers, directors, designers, and technicians keep plugging away at their various arts, with or without reasonable financial recompense, obituaries seem premature.

One final note: George Bernard Shaw once observed that theatrical economics can never really be rationalize because when theaters are making money, they’re making it so fast that economy seems irrelevant; and when they’re losing money, they’re losing it so fast that no amount of economy will help. Or, to put it another way: they say bumblebees are too heavy to fly. But the bumblebees don’t know that, so they go on flying anyway.