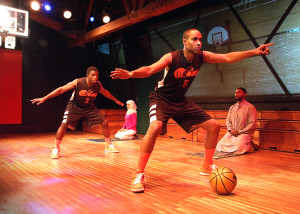

Full-Court Press

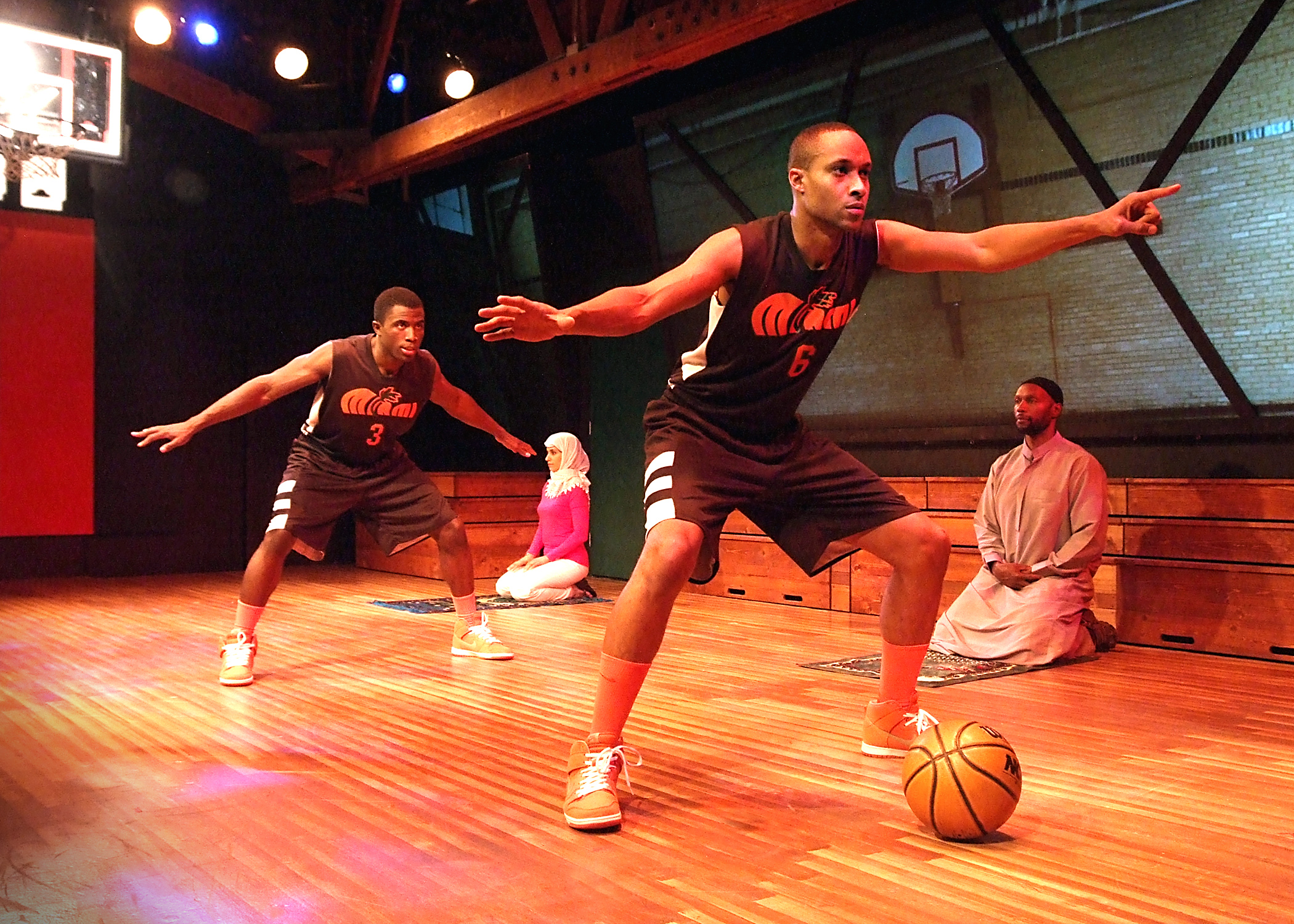

First-time-playwright Amir Abdullah discusses Islam, basketball and friendship in his Pray to Ball at the Skylight Theatre

By Deborah Klugman

Amir Abdullah’s first play, Pray to Ball, opened last weekend at the Skylight Theatre. A writer and actor, Abdullah grew up in Jacksonville, Florida, earning his BFA from the University of Miami and his MFA in acting from Penn State University. Following graduate school, he arrived in L.A. in 2010. The play deals with college sports and religion, and pivots on the lifelong bond between two college basketball players and what happens to their friendship when matters of faith come between them. It also spotlights hypocrisy and prejudice, and the conflicts and trials faced by American Muslims today. Abdullah also performs in the play.

The drama was developed through Skylight’s Theatre’s INKubator program for new works, under the aegis of the company’s artistic director, Gary Grossman.

STAGE RAW: Tell me about the story and the characters.

AMIR ABDULLAH: It’s about two superstars, college basketball players. The main character is an incoming freshman named Hakeem. The antagonist’s name is Lou. He’s a sophomore. He’s been there one year and has been waiting for his buddy to come. These two guys that have a strong bond that goes beyond the court, that goes beyond what we see. They are planning to play together [in college sports] for one year and then go to the NBA, be millionaires, have a wonderful time. It’s been their plan since high school. But plans don’t always work out the way you want them to.

SR: Is Hakeem a Muslim?

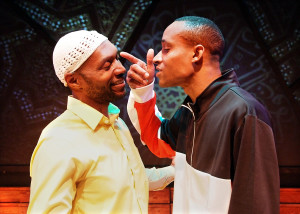

AA: No, not at the beginning. Hakeem’s mother dies and he’s thrown for a loop. He’s searching for something to grasp onto. And he’s drawn to Islam. Eventually he gets more into it and that causes problems with Lou. It’s a complete turnaround from everything they planned and had wanted to do.

So the main conflict is with Lou over his conversion to Islam?

Not entirely. There are a lot of things he goes through once he’s converted to Islam. He starts to see cracks in the armor of the followers of the religion. He sees a lot of hypocrisy. And so he has to decide whether he’s going to stick with it or go back to his old life. It’s a crisis that involves trying to find something that he can hold onto and believe in – but seeing that it may not be right. I think that’s something that everyone at some point in their life deals with.

What drew you to this arena?

Number one, I’m a big fan of sports. I’m interested in the culture that surrounds college athletes, the kind of day-to-day work these guys have to put in and their team dynamic. And I’m interested in the way they are perceived by the fans. These kids are 18. And you have 45-, 55-, 60-year-old-men following their every movement. But these kids are not necessarily looked at as human beings. They are looked at as a number on the back of a jersey. [The fans] don’t really care about the kid. All they care about is the performance.

That was the spark. And then I wanted to explore the religious angle, offer some insight. We see what goes on with Muslims on TV, but how many people have actually talked to a Muslim or attended a service. So for me it became: How can I merge those two?

Were you ever a ball player?

No, I was a theater major in school. But a friend of mine who played on the team at the University of Miami, Cyrus McGowan, was willing to open up to me. He was instrumental in hammering out the finer details of being a basketball player at a big university.

You said that you wanted to give people some insight into the Muslim experience but you also said Hakeem had some negative experiences with some of the other folks within his religious circle. Do you think people might take away something negative?

No. I think people will see a complex relationship, a complex view of religion. I don’t want this to be a passion piece. I don’t want to damn it either. There’s a gray area. Every religion, every ideology, every political party has its own messy things that are part of it. And I’m not doing my job as a storyteller if I don’t show the full picture. Not just the view on something like 24 where every Muslim is a terrorist. And not every Muslim is squeaky clean. You gotta show what’s in the middle.

Writing a play is a difficult and ambitious undertaking. What made you decide to attempt it?

When I was in graduate school at Penn State, I had some very influential professors. We were studying acting but they also pushed us to do something beyond that. They always told me, you have to write. You have a story to tell. That thing just resonated with me. And so I wrote from what I knew. I know Miami. I know Florida pretty well. I know sports. I know Islam. So in some ways it was natural to do this.

You’ve published a brief writer’s commentary about the play on Skylight Theatre’s website. It indicates that you feel that the voice of the Muslim-American artist doesn’t get enough expression in our community. Am I correct?

Yes. I’m talking about artistic expression as it relates to dealing in everyday life.

There’s no Muslim-American artistic tradition?

You are pushed away from it. A lot of American Muslims are pushed into careers like doctors, lawyers The goal is to support a family. And to support a family, you want to be in something with a high success rate That’s great. But……

But isn’t that cross-cultural? I experienced the same thing in my tradition, which is Jewish.

But the difference is – if I attend a Seder, we’re singing songs, we’re story-telling. That’s intrinsic in the belief. The Holy Koran is very melodic, but an exploration of what’s going on in everyday life — that is not explored. Secular music is not encouraged.

What about visual art?

It’s limited. Religious calligraphy, that sort of thing. And when it comes to the stage: as far as American Muslims go, we don’t do it.

So one of the things you want to say is that artistic expression is not encouraged among Muslim Americans and should be?

Yes. The Imam at the mosque isn’t necessarily going to tell me everything that I need to know.

And you’ve found some of that in the theater?

I’ve learned so much from being in the theater. I’ve gained so many different perspectives.

Have you encountered prejudice in your personal life?

Absolutely. I personally don’t identify with the Muslim stereotype, but I have my name. It’s on my passport. It’s on my license. There’s always the extra screening and being detained at the airports. Or people will make comments or we’ll have eggs thrown at us. My parents are very orthodox and very visible in the community in Jacksonville, Florida. There have been bomb threats at the mosque where I grew up.

I used to wear my religious hat in high school. In middle school, I used to wear a kufi. I did my best to identify as a Muslim. But the world changed for everybody after 9/11. I remember distinctly somebody saying to me, “I hope your family didn’t have anything to do with this.”

How old were you then?

I was 15-years-old when that tragedy happened. And people tend to look at you unfairly. That’s the reality. It’s like being the only black kid in class or the only Jewish person in town. Fairly or unfairly, you have to be the voice of your people.

What do you want people to take away from your play?

I want this play to be accessible to everybody, regardless of ideology. I want everyone to be able to take something away. For most of the people coming in to see the show, they know most of it, the journey that it takes. For them, hopefully I am holding up a mirror to our society so that they can see the hypocrisy, what we do to push people away. For a non-Muslim audience that is less informed about the religion or has never met a Muslim, I want them to be in that world and be exposed to it. There are a lot of different layers to this play. Everyone is going to take something different away.

Pray to Ball is being performed at Skylight Theatre, 1816 ½ N. Vermont Ave., Los Feliz; Fri.-Sat., 8 p.m.; Sun., 2 p.m.; through June 8. https://skylighttheatrecompany.com

Also, read Lovell Estell III’s review.