What Means “Professional?”

Joseph Stern, on the 99-Seat Plan and the hidden politics of the L.A. Stage

By Guy Zimmerman

“If you get rid of the 99-seat movement you kill 80 per cent of the theater in L.A.”

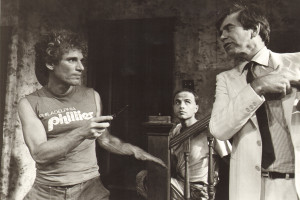

This is how Joseph Stern, Producer of the Matrix Theatre Company, puts it. Along with Tom Ormeny of the Victory Theatre and Simon Levy of The Fountain, and a few others, Stern has for 40 years been among the most committed and effective defenders of a creative community – L.A. theater – undervalued even by most of its members. Through an extended series of dramatic battles and interventions stretching back to the late 1970s, Stern and his cohorts extracted from the stage actors’ union (Actors’ Equity Association) the nuts-and-bolts standards and agreements (originally known as the Equity Waiver Contract, which has since evolved into the 99-Seat Theatre Plan) that have made the city arguably the most fertile creative ecology in American performing arts.

Before these battles, Union actors were simply forbidden from performing on any stage without receiving Union wages and benefits. The result of that policy was a cultural desert – the vast majority of producers simply couldn’t afford to put on plays. Meanwhile, actors who were between TV and film jobs wanted to work, to keep their skills sharp, and they said so to their Union. Their initial victory in the battles that became knows as the “Waiver Wars” was a concession by the Union to “waive” a number of Union protections (wages, health care contributions by their employers, etc.) while certain health and safety provisions remained intact — if these “waiver” productions were staged in venues of 99-seats or less. The Union’s rationalization was that in theaters with such small seating capacity, producers wouldn’t be able to profit in any exorbitant way off their members’ labor. Furthermore, this “waiver” allowed for agents et al to see the actors in performances they otherwise couldn’t. Hence, the Equity Waiver Contract was supposed to provide employment opportunities for work that was more lucrative.

This “opportunity” turned out to be largely illusory, for any number of reasons. insomnia. The more palpable consequence was an explosion in the numbers of small theaters across the city, created in storefronts and converted garages, and many doing exploratory work for reasons the East-Coast-based Union found incomprehensible.

In the intervening years, the Contract has been revised, mandating an increasing scale of token payments to actors for performances, and growing restrictions on the duration of a “Waiver” show’s run.

And yet, as strong as ever is the tendency in the culture to dismiss 99-seat L.A. theater as unprofessional, a tendency that was set 40 years ago in the initial battles Stern and company fought with Equity’s western regional director Edward Weston.

Stern personally fended off what he describes as Weston’s efforts to sabotage his production of Eric Bentley’s Are You Now or Have You Ever Been in 1975 and Harry’s Lies and Legends at the Improv in 1977, he then participated in the lawsuit against an infamous referendum issued by Weston in 1988 dissolving the Waiver — a lawsuit that laid the groundwork for the Settlement Committee that must now agree to all changes to the agreement. And yet, despite all this activism, Weston’s dismissive attitude towards Waiver theater continues to percolate in the broader culture, where it has encouraged everyone from the L.A. Times to the leadership of the area’s larger theaters to diminish the achievements of the community strictly because of ersatz issues relating to payment.

As the producer myself of dozens of new plays in Los Angeles, I’m speaking about Stern as one of many beneficiaries of his pugnacity and clear-sightedness, and also as someone interested in the larger political dynamics at work in an arena I know well.

Rumors are currently swirling about impending changes to the 99-Seat Plan. While a member of the original Review Committee set up through the court settlement in 1989, Stern will not comment directly on these rumors, he remains convinced that the underlying dynamic can only be understood in the context of the Union’s home base across the continent in New York City.

“They never understood conceptually anything about the topography” of Los Angeles, he says. Stern has in mind L.A.’s unique theater culture, which is shaped by the collision between abundant talent and endless traffic. On the one hand, despite a population density that matches many areas of New York, Southern California lacks the mass transit infrastructure that enables a vibrant theater scene. To invite someone to see a show in Los Angeles also includes inviting them to a traffic jam and parking problems.

On the other hand, this suburban landscape is also freakishly saturated with creative talent – actors, writers, directors and designers – the most diverse and energized creative community on the globe, and all that talent generates a diversity and intensity of expression you can’t find anywhere else. The city provides something analogous to the Open Source platform in the info tech industry – a fantastically vibrant hotbed, or incubator, in which new theatrical forms arise and propagate and stagger off toward New York and Europe.

In Stern’s view, the root of Actors’ Equity’s animus to L.A.’s 99-Seat Plan is New York City’s anxiety about its position at the center of American cultural life. “L.A. has everything,” he says, “particularly film. All they have is the theatre. So it’s in their interest to invalidate us. This is what I firmly believe.”

With a semi-conscious determination, according to Stern, the Union has for years wanted to dissolve the Waiver contract that has allowed L.A. to pose a mortal threat to New York’s final claim to cultural relevance – theater. And yet a cursory look at urban development and redevelopment shows how Los Angeles, far more than New York, has for decades provided the national model for how cities have developed in America — I mean the sun belt cities of Atlanta, Dallas, Huston, Phoenix and Las Vegas, for example — such that L.A. theater speaks with greater accuracy about where the nation’s values clash, and where meaning can still be found. It is not simply that L.A. straddles the line between suburb and city, it’s that it does this while also being defined by a saturation of theatrical talent, allowing expression where ordinarily expression would not take place.

The racially sequestered, automobile-centered (as opposed to mass transit enabled) nature of the typical urban environment of the U.S. is precisely what you encounter in L.A. as opposed to New York, which feels more like a European city in this regard. Living in Los Angeles, the theater artist (playwright, director or actor) encounters this reality daily in ways that percolate into the work.

Any description of L.A.’s theatrical prominence might seem surprising, but only because the Angeleno roots of so many new theater productions have been so carefully hidden over the decades. Stern has endless stories about the lengths playwrights and producers have gone to cover their Angeleno tracks – Simon Gray with A Common Pursuit, John Patrick Shanley’s Italian American Reconciliation, which was developed in the 1980s with Joe Pantoliano in the San Fernando Valley, and the recent refusal of New York producers to acknowledge the Matrix Theater’s claim to the original production of Lyle Kessler’s Orphans.

“It comes from Longwharf? Hey, it’s on the front title page of the program!”

This may also have to do with the deeper legend of L.A.-as-cultural-desert, from the oft-told stories of how badly distinguished writers – The Mann Brothers, Bertolt Brecht, F. Scott Fitzgerald – were treated here.

In 2014, there’s no difference, to Stern, between L.A.’s actors, directors and designers –who’ve been known to mount world quality material — and their East coast counterparts.

“By calling us amateurs,” he says, “it enables them to maintain their status which only became more threatened when the East Coast artists (actors, etc. but more importantly the playwrights) emigrated to L.A. in search of a living wage that ironically they couldn’t earn in the N.Y. theater and the regional theaters.”

Much of the time, theater artists working in the two cities are the very same people – the only difference is how their work is framed.

What goads Stern most – and this is where the political aspect lies – is the unspoken logic behind the constant denigration of L.A. theater by the Union that should defend it. This is how Stern encapsulates the Union’s attitude:

“If actors don’t get paid then they don’t have any real rights. And also they’re not professionals because professionals get paid.”

When you produce a play in Los Angeles, it is extremely unlikely you will make your money back. Think about what an anomaly this is: almost all of us have internalized the idea that financial motivations explain the choices we make at every level of our lives, an idea that has been embraced with religious fervor by many of the most powerful, and that you can see paraded with chest-thumping vividness on Fox News every night of the week. So in a culture that since the Reagan era has been dominated by the idea that the marketplace is the only true arbiter of value, L.A. theater operates without any regard for the quasi-religious imperative to follow the dictates of the spreadsheet. This imperative has a paranoid edge to it – the domination of market-place thinking has to extend to everything or its basic claims are invalidated – in Margaret Thatcher’s immortal words “There Is No Alternative.”

The larger question, is whether the fate of theatre in Los Angeles can be linked to larger trends in American culture, such as the concentration of wealth and power among the top one per cent. In my lifetime I’ve watched this segment of the population methodically decimate the American middle-class – and speaking selfishly I’d prefer to preserve my ability to shine a light from the stage on what they are doing.

Likewise, as the L.A. theater community considers revisions to the Contract with a partner who does not share core values, the question is whether or not to knuckle under and kiss the glove, accepting a logic designed to suppress the expressive exuberance of L.A.’s remarkable creative community. As allergic to politics as our culture has become, it seems difficult to sidestep the political in this fight. Until now, the behind-the-scenes work of Stern and his colleagues has created a unique alignment of forces, and it’s probably time for the rest of the community to wake up and smell the cat food.

Guy Zimmerman is a playwright and director. Since 2001, he has been the artistic director of Padua Playwrights

Editor’s Note: AEA’s recent removal of Union rep Michael Van Duzer, who, for decades, massaged the changing terms of the 99-Seat Plan in a way that preserved L.A.’s hundreds of small theaters, does not appear to bode well for the security of the Plan, or the theaters under it.