A Web Series about a Shakespeare Competition?

The Long and Winding Road to Hulu’s Complete Works

By Mayank Keshaviah

“He that will have a cake out of the wheat must needs tarry the grinding.”

This bit of advice from Pandarus in the opening scene of Troilus and Cressida is equally apt to describe the lessons learned by the creators of Complete Works, a new Hulu comedy about a Shakespeare competition that celebrates the bard in quirky and clever ways. How that show came to be, and how it made it to Hulu is the story of the independent filmmaker in the “new Wild West” of digital media.

In one sense, the show’s journey began in 2004, when its co-creator Joe Sofranko won the National Shakespeare Competition at Lincoln Center as a high school junior. He had made it to New York from Ohio, standing out from a field of over 16,000 competitors nationwide. (The show’s central character, Hal, hails from Indiana.) A year later, as a senior, Joe traveled to Miami, Florida, for the YoungArts competition, where he first met his co-creator and current girlfriend Lili Fuller, who hails from Los Angeles. The two collaborated (and dated) while studying theater at USC. They also became friends with English Lit major Adam North, the third member of the triumvirate behind Complete Works.

Fast-forward four years, through scene study classes, student productions, the formation of a dance troupe, and college graduation. Sofranko and Fuller found themselves in the same place that so many other young actors do in this town: performing in a play here and there, landing an occasional commercial and maybe even a bit-part in a TV episode. While walking home from a Coffee Bean one day, craving a more sustainable creative outlet and some control over their careers, the pair came up with the idea of creating a show about a Shakespeare competition.

Having had firsthand experience with the oeuvre, the two were interested in the backstage dynamics of an arts competition because they believed it was yet unexplored in narrative fiction.

“When you are in these situations,” Sofranko says, “everyone’s best friends and it’s kind of like a camp, but then underneath that there’s this underlying tension like everyone’s looking to see who’s the best.”

In fact, when the two returned to YoungArts as Resident Advisors in 2013, Sofranko recalled a situation in which he was doing a bed check for one of the participants and was asked by the young man, “So, are we being judged all the time?”

Sofranko relates the anecdote because that sense of anxiety became one of the themes of the show: the idea that you don’t really know when you’re being judged, or how you’re being judged, but you really are being judged all the time.

Sofranko wrote a rough draft of the “pilot” in 2010, recalling that it was “bad” but not “bad enough” to be dismissed by North, who was initially consulted only for notes and feedback. North recalls that Sofranko at the time wanted to “make it really fast, shoot with our friends, and…get it online.”

North also mentions that at the end of their first meeting on the project, there was a moment that now “feels so fateful.”

As they were walking to their cars, Sofranko said, “This was fun” and North responded offhandedly, almost automatically, “We should do this again.” Now four years later, the three of them heartily laugh at this moment of fortuitous happenstance.

Sofranko and North worked for about a year on the script, and while doing do, the trio also began fundraising, which included an Indiegogo campaign, solicitations of friends and family, bank loans, credit cards, a contribution from ETC Theatre Company and personal funds, such as money Sofranko made from a Wendy’s commercial. Their crowdfunding campaign only raised about a fifth of the approximately $45,000 budget, so it’s not surprising that they only paid off their personal credit card bills from it this past February.

These are the slings and arrows of independent filmmaking in the digital age.

Having navigated the initial gauntlet of challenges, and having formed their production company, Kingdom for a Horse Productions, the group selected a director early in 2011, with aims to shoot that summer. They parted ways with that first director, a more experienced one, because of different visions on the scope of the project.The second was a USC friend who loved the script and gave some valuable notes, but he ended up with too many other responsibilities to be able to commit to the project. Two weeks before beginning shooting in September of 2011, the third director, who had only come on a week earlier, felt the team wasn’t ready and ended up dropping out as well. This series of unfortunate events, which left the trio deflated and upset, ended up being a blessing in disguise because, as they now realize, they really weren’t ready.

So, somewhat against their, um, will, they tarried the grinding. The next year was spent raising more money, refining the script, and finalizing the casting. Sofranko and North decided to direct the project themselves, since they understood it better than anyone they might bring in. They also began working with Dr. Gideon Rappaport, a Shakespeare scholar from San Diego who was initially approached for funding in 2011, but who ended up lending his expertise to the team, serving as the project’s dramaturge and Shakespeare coach.

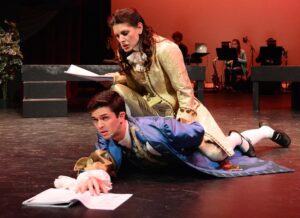

Even prior to Sofranko and North deciding to direct, the show had been written around actors they knew, including Ben Sidell (as Ian), Lizzie Fabie (as Regan), and of course Fuller (as Pauline) and Sofranko (as Hal). But auditions were held for a few of the other principals such as James (played by Kevin Quinn) and Oliver (played by Chase Williamson), and for a number of the supporting roles. The story behind casting the character of Leo is particularly interesting because Sofranko and Fuller originally had in mind British actor Luke Youngblood, of Harry Potter fame, who had been their downstairs neighbor. Once the shoot was pushed back a year, however, Youngblood had moved back to London, so, just in case, they held auditions for Youngblood’s role. Alex Skinner was the first actor they saw, and he “killed it” in the audition and “had a perfect British accent” according to Fuller, so once Youngblood became unavailable, Skinner was the natural choice. The ironic thing was that Skinner had first read for them in 2011, and he had not received a callback for a year. As Sofranko puts it, “when actors say ‘I didn’t get it’…you never know.”

In finally shooting the show during the summer of 2012, they were “thrifty and scrappy,” as Fuller says, “but also at the same time [were] trying to have as much legit equipment as we could.” Much of the 20-day shoot took place in Ranchos Palos Verdes at a property that once belonged to Fuller’s grandmother; the remaining Southern California locations were obtained gratis through favors called in. Among the challenges they dealt with were climbing down to Thousand Steps Beach in Laguna with their equipment for the “worst day of shooting,” having to “hold for peacock” during shots because the birds that roamed the RPV property had exquisite timing, and a silk lighting screen that nearly fell onto Sofranko during a windstorm.

They learned how to make filming schedules from YouTube videos, copied other productions’ call sheets, and even built the amphitheater stage used in the show with help from friends, family, and volunteer construction workers, such as production designer Alicia Papanek. At one point, Papnek even suggested dumpster-diving to fulfill their craft services needs, but Sofranko and Fuller balked at the idea, finding other ways to cut costs that wouldn’t risk illness and disease.

After months of editing and scoring, post-production was completed in October of 2013, at which time they had 14 episodes, seven to 10 minutes in length. Because landing distribution rights through Hulu was a pipe dream, they segmented the episodes so that they could be uploaded to YouTube as a backup plan. YouTube was considered a backup because Sofranko felt the show’s subtleties would get lost in the outlandishness and white noise of the site. He really wanted an outlet that “supports attention spans.”

Through perseverance, the trio eventually garnered interest from a big-name agency, but once that agency failed to find them a landing spot quickly, it moved on from their project. Disappointed, they nonetheless willed themselves to continue, as they had come too far not to. “It took almost a year of just straight hustling every day,” says Sofranko.

During that year, because the digital space was still so new and constantly changing, they often received conflicting advice as to where their show would fit best and whom they should approach. Navigating this “Wild, Wild West” of entertainment was therefore confusing. At one point, they were even advised to re-cut the show as a feature film and submit it to festivals. However, they forsook that route because of a belief in the greater reach of the Internet, whose audience was more their style. They ended up meeting former USC classmate Lisha Yakub at an alumni barbecue, and she was so excited by the project that she wanted to be their manager. They clicked with both her and their eventual agent at CAA because each of them was young, still had something to prove, and was willing to hustle: not so green that they had no clout, but not so arrogant as to dismiss a project like Complete Works.

Through persistence, they got their project into the right hands at Hulu, and after re-cutting the show into five 30-minute episodes (Hulu prefers its content longer) and after about five months of internal development, Complete Works was released on the the day of Shakespeare’s 450th birthday, April 23, 2014, four years after the trio first began work on the project.

Looking back on their process, the creators believe digital media facilitated their getting the show distributed because a company like Hulu has an acquisitions department looking for new material, whereas a network or cable outlet would never have even considered such first-time filmmakers. At the same time, Hulu’s hallmark of quality appealed to them. It also didn’t hurt that Hulu had no similar shows in its lineup. In a way, Sofranko says, web series are a new, better version of the film festival because of the potential audience due to the Internet’s reach.

“It’s weird to be like, this is a dream, and then we made it happen,” says Fuller. In fact, about a year back, cast member Skinner had jokingly made a mock up of what their show would look like advertised on Hulu’s website and texted the picture to Fuller, who, not wanting to jinx the show’s prospects, asked Skinner not to share it. Instead, she made it the background image on her smartphone, vowing not to remove it until it became reality.

But having gone through a four-year process that led to that reality, the team learned some valuable lessons. Fuller’s advice to other would-be filmmakers would be to not “be afraid to ask questions or reach out to people, because somebody knows the answer or you’ll be able to find it, and people are willing to help.” Sofranko’s advises, “don’t sacrifice at any step of the way” in terms of quality and standards, because if you do, “you’re going to regret it when you’re editing.” He also says that “inspiration for . . . passion projects can die very quickly,” so once you get into the second or third year of a project, you need to “trust that the passion is still there even on days when you don’t feel like it.”

North’s take is to “have a little gumption and make something that you care about and be committed to quality. We took the slower route, but by taking the slower route and making something that felt like it was of higher quality, it really paid off.” Sofranko calls it the “ultimate lesson in patience and perseverance . . . especially in a world that’s very much about instant gratification.” Indeed, tarrying the grinding is what made this cake of wheat rise.

Complete Works, Kingdom For a Horse Productions, is available on Hulu

Jenny Lower reviews Complete Works on Stage Raw.