The Mildest-Mannered Flame-Thrower in Los Angeles

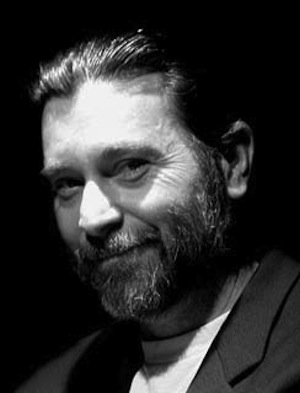

City Garage’s Charles Duncombe

BY STEVEN LEIGH MORRIS

Imagine, the playwright-actor Molière in his 17th century theater being grilled by a grants officer from France’s National Endowment for the Arts. The officer asks Molière to provide empirical evidence of whom his plays are reaching, cost versus expense ratios, and which kinds of plays are the most popular. What was once simple patronage by the King Louis XIV – funding had its own drawbacks, including the need to grovel – has now turned into a government grants dance (a different kind of groveling). Bend the art to obtain the funding for it. Prove your case with survey results. Google Analytics doesn’t actually come up in this scene, but it could.

“When they like the play they applaud,” Molière explains, dumbfounded, to the grants officer. “When they don’t, they throw things.”

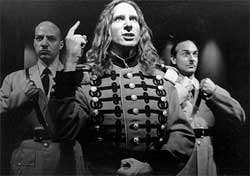

This kind of joke forms the essence of playwright Charles Duncombe’s satirical wit. A few critics of this repartee contained within Duncombe’s latest play, Bulgakov-Moliere (at City Garage in Bergamot Station through June 1), snorted contemptuously at the anachronism, but shuttling ideas from the 17th century into the 21st is precisely what Duncombe does, and has been doing for decades in his tenure as City Garage’s resident playwright, designer and Producing Director.

In 2001, Duncombe adapted Heiner Müller’s Frederick of Prussia into a work with a coda in the title: George W’s Great Dream of Sleep. An actor playing the former pres sat above and behind the historical drama about the brutal Frederick, and dozed off. A week into the production came the 9/11 bombings of the World Trade Center; the subsequent tragedy and related waves of patriotism compelled City Garage to cancel the show. Sometimes theater changes the world, sometimes it’s the other way around.

Duncombe’s partner, Artistic Director Frédérique Michel, stages all the works at City Garage. The pair have been putting on abstract yet mostly politically charged theater for decades. Early on, they presented plays by Harold Pinter in a makeshift theater on the Santa Monica Pier. For many years, they leased a former city garage (converted into their theater) off an alley behind Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade. After that arrangement ran dry, they converted yet another Santa Monica space in Bergamot Station

My admiration for them stems from their defiant determination to do plays that only a minority of Americans had even heard of, and to put on adaptations, written and designed by Duncombe, of heady works by the likes of Müller, Caryl Churchill, Sarah Kane and Reiner Fassbinder, to throw politics all over their stage like confetti.

With the possible exceptions of China and Russia, the United States is the only place where discussing politics in the theater is considered a delicate matter — even through parody. This is particularly odd given the popularity of overtly topical, political satire on TV shows such as The Daily Show and The Colbert Report. These shows are serving exactly the same, politically mocking role played by the likes of playwrights Vaclav Havel in communist Czechoslovakia and Athol Fugard in Apartheid South Africa. The hostility to politics in our own theater is baffling. Duncombe knows all this.

“It’s a peculiarly American idea that politics is divorced from art,” says Duncombe. “That theater isn’t responsible for provoking a dialogue – how dare you bring politics into art. It just doesn’t belong in the theater. You go into the theater for emotional voyeurism.”

And so he continues to insert political satire and indignation into his plays and adaptations. Duncombe is almost like some Monty Python character who taunts any Goliath or drama critic who’s hanging around – go ahead, hit me, beat me. Just try it!

Through most of 2012 and much of 2013, Duncombe and Michel worked with me on a new version of my play Moskva – a contemporary adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita set in Putin’s Russia. (The theater staged the play at the end of 2013, and it was initially supposed to be performed in repertory with Bulgakov-Molière, until Duncombe and Michel came to the realization that they simply hadn’t the human or technical resources to pull off such an ambitious pairing.)

During much of the time we were discussing rewrites, Duncombe was enduring the tortures of throat cancer treatment – brutal radiation — with an attitude somewhere between stoicism and good cheer. Somehow, when we met then, he just shrugged off the side-effects almost cheerfully. It’s not that he avoided the topic but he was quick to change the subject.

Duncombe is living proof that much of L.A. theater is not an attempt to woo the film and TV industries that still dominate our cultural landscape. Rather, the theater is a reaction against it, what playwright Jon Robin Baitz famously called “an antidote to the toxicity of living in a company town.”

How bizarre it must be for Duncombe to leave performances of Bulgakov-Molière to attend his day job for ABC as a writer on a reality show.

Duncombe’s Bulgakov-Moliere is a multi-layered fantasia about the somewhat dissolute Russian novelist Bulgakov grappling with Stalin about what was allowed in Soviet art, and what was not. For his part, Bulgakov wrote his own play about that equation. It was called Molière, and it studied that playwright’s troubled relations with the Catholic clergy in Paris (who didn’t like his plays at all), as well as with the French King, who did like his plays but who was beholden to the Church. The king was also Molière’s sponsor and employer. Bulgakov was looking at Stalin’s policies through the prism of artistic tyranny in 17th century France.

In Duncombe’s play, Bulgakov is dragged away by the KGB to a theater, in order to watch a production of his own play, Molière, and perhaps to learn something from it. The heart of the matter, for Duncombe, comes from an emblematic line in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, “Cowardice is the greatest of all human vices.”

There’s a certain mythology about the bravery of people standing up to dangerous authority, facing the risk of prison or death – playwrights Vaclav Havel, Athol Fugard, the Soviet troubadour Vladimir Vysotsky, and countless journalists in Putin’s Russia. Duncombe takes the view that Bulgakov – though as brilliant as novelists come – was not in that same moral company, that he was doing what was expedient to save his own skin.

Explains Duncombe, “When we collaborated on Moskva, I went back to do more research and became more invested in Bulgakov’s personal biography, what he was going through in his life, and I realized there was this critical moment in his life:

“Molière had just been banned, [Bulgakov] was writing to Stalin to appeal. He had, at that point burned his only copy of The Master and Margarita. I thought, what a great launching point to have him fall asleep – Woland [the devil in M&M] appears in a distorted version, poking and prodding him with issues that Bulgakov struggled with through his life – the artist’s obligation to stand up to the State, free expression. He didn’t. And that’s what’s so interesting. I think that’s why he was obsessed with the idea that cowardice is the worst of all human vices.”

Duncombe says that he wanted to focus on Woland needling Bulgakov “on the issue of his own lack of ability to stand up to the Soviet State, to Stalin, to the censors. He’s not willing ultimately to be a dissident artist. He feels neglected. He doesn’t have the courage to be the man he wants.”

There’s also a right-wing American radio broadcaster and born-again Christianity referenced in the play “The relationship to America isn’t exactly parallel,” says Duncombe, “but the polarized dialogue over the place of religion in politics, and American attitudes toward religion, have interesting parallels to Molière’s time.”

Some critics found those characters gratingly out of place. Not so Stage Raw’s Lovell Estell III, whose review is here

There is, in fact, a place for politics in American theater, in certain constrained circumstances. Take, for example, the many plays honoring singer/social crusader Paul Robeson on our stages over the past few weeks (including Philip Hayes Dean’s Paul Robeson at Ebony Rep, and Daniel Beaty’s The Tallest Tree in the Forest, now at the Mark Taper Forum.) They tackle the delicate business of glorifying a labor-rights activist and communist sympathizer with a defiance that matches the defiance of their central character. These are studies in American heroism.

Duncombe is defiant in exactly the opposite way, writing a play about an artistically brilliant central character who failed to live up to his own moral standards. City Garage has a habit of doing anti-heroic plays. It’s just how they see things, in opposition to the way most of us want to see things in the theater, which is what Duncombe calls “emotional voyeurism.” Now that’s defiance.

Bulgakov-Molière continues this weekend at City Garage, Building T1, Bergamot Station, 2525 Michigan Ave., Santa Monica; Fri.-Sat., 8 p.m.; Sun. (pay what you can), 5 p.m.; through June 1. (310) 453-9939, www.citygarage.org