Remembering Ron Sossi, Gordon Davidson, and Their Era

Spirit Guides

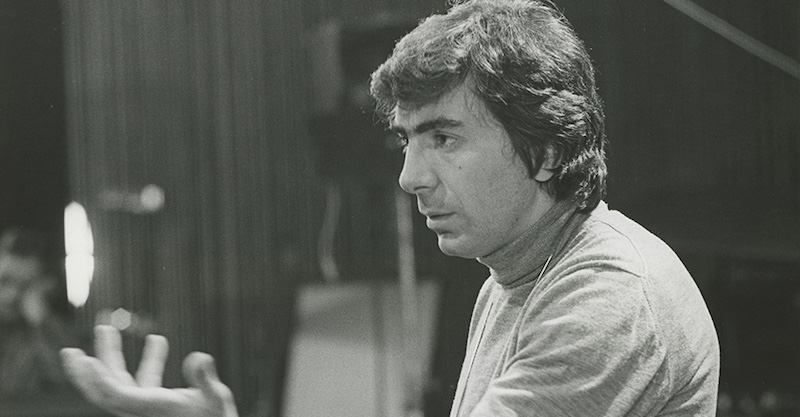

Ron Sossi’s passing last week marks a milestone for Los Angeles theater, because he joins Gordon Davidson in the pantheon of preeminent spirit guides for our stage community. The pair are now truly spirit guides — not just because they were spiritual forces when they were alive, but because they’re actual spirits. Prior to the 1970s, Los Angeles was a minor touring production destination. By the turn of this century, thanks in large part to the efforts and influence of Davidson and Sossi, Los Angeles theater had/has become a creative force that develops new work, uses innovation and imagination in devised work, and sometimes sends that work across the nation and abroad.

To be clear, there are other L.A. theater spirit guides from the 20th century and the dawning years of this century, and some are still very much with us. In the arena of new play development, there’s Jon Lawrence Rivera and his Playwrights Arena; Martha Demson’s Open Fist Theatre; Jessica Kubzansky and her Boston Court Theatre; Josefina Lopez’s CASA 0101; Gary Grossman’s Skylight Theatre; Sam Anderson and Taylor Gilbert over at Road Theatre Company; Maria Gobetti’s Victory Theatre (her co-founder-husband Tom Ormeny died in 2023); Ben Guillory’s Robey Theatre Company; Jose Luis Valenzuela’s Latino Theater Company; Tim Robbins’s The Actors’ Gang; Marilyn Fox’s Pacific Resident Theatre; and Chris Fields’s Echo Theater.

In the Department of Classics, continuing their tradition of accomplished productions, are Julia Rodriguez Elliot and Geoff Elliot’s A Noise Within; David Melville and Melissa Chalsma’s Independent Shakespeare Company; and Ben Donenberg’s Shakespeare Center of Los Angeles.

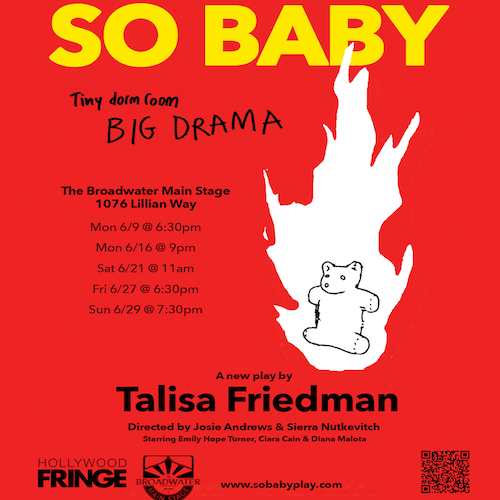

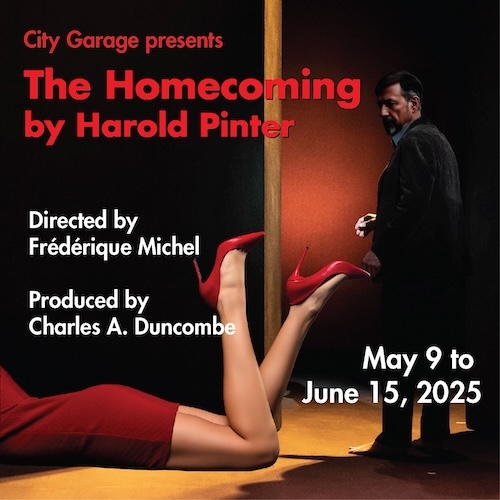

In the Department of Devised Work (and other non-traditional approaches) there’s Mark Seldis and Katharine Noon’s Ghost Road Theatre Company; Matt Walker’s Troubadour Theatre Company; Frederique Michel and Charles Duncombe’s City Garage; Nancy Keystone’s Critical Mass Performance Group; and the ghoulish aesthetic of Zombie Joe and Denise Devin of Zombie Joe’s Underground.

Along with people who served as bulwarks for introducing playwrights to L.A. as well as producing classical and devised works, some are gone, some living but no longer engaged creatively in the field: Quentin Drew and Lynn Manning’s Watts Village Theatre Company; Steve Kent and Gar Campbell’s The Company Theatre; John Smith (“Smitty”), a New Orleans native who created a performance venue (The Fifth Estate Theater) next door to the Déjà Vu Restaurant and Coffee House on Kenmore Avenue in East Hollywood: For $7, a theatergoer could see a play and have a cup of cocoa or hot cider; C. Bernard Jackson and his Inner City Cultural Center; Murray Mednick and Guy Zimmerman’s Padua Playwrights, first conceived as an outdoor summer festival of new works staged in the hills above Claremont; Ted Schmitt and Diana Gibson’s The Cast Theatre on El Centro, that made a cottage industry of plays by Justin Tanner; Carmen Zapata’s Bilingual Foundation of the Arts, dedicated to classical works presented in Spanish and English; Frenchwoman Rachel Rosenthal, an animal rights activist known for her pet rats, was a performance artist who formed a company for devised work, and Frenchman Paul Verdier operated a tiny Hollywood venue dedicated to French classics — he frequently had his friend Eugene Ionesco in residence.

The Padua Playwrights Festival, Claremont, CA, circa 1983. Murray Mednick far right. (murraymednick.com)

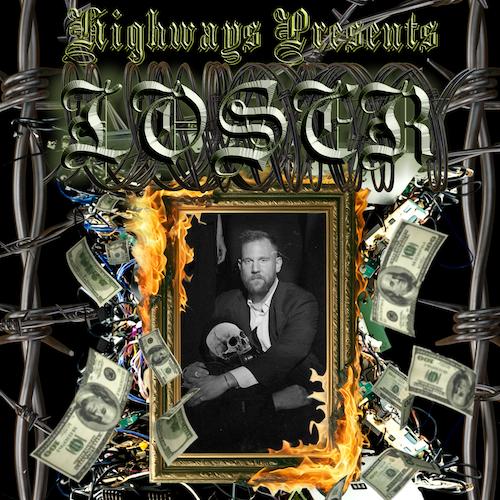

Linda Frye Burnham and performance artist Tim Miller’s Highways Performance Center became the hub of gay-themed work in Santa Monica, along with the Celebration Theatre, which produced from venues in both Silver Lake and Hollywood. This is a mantle since taken over by the Los Angeles LGBT Center in Hollywood; The ProVisional Theatre of Los Angeles; Peg Yorkin’s L.A. Public Theatre operating out of The Coronet Theatre on La Cienega, north of Beverly Boulevard. That was the same venue that had housed the national premiere of Bertold Brecht’s Galileo (1947-1948) with Charles Laughton, during Brecht’s brief, unhappy residence in L.A.; Stephen Sachs and Deborah Lawler’s much storied Fountain Theatre (still going strong) that landed the world premiere of Athol Fugard’s Exits and Entrances in 2004; Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum (still going strong under the leadership of Geer’s daughter, Ellen Geer); John Flynn’s Rogue Machine (still going strong); John Sylvain’s Sacred Fools Theater Company (still going strong); Estelle Bush’s Synthesis Theatre Company, Joe Stern’s Matrix Theatre; Laura Zucker’s Back Alley Theatre; Paula Holt’s Tiffany Theatres; Bill Bushnell and Diane White’s Los Angeles Actors’ Theatre (which transitioned into the Los Angeles Theatre Center, now administered by Latino Theatre Company); Barbara Beckley’s Colony Theatre; and The Antaeus Company’s founding artistic directors Dakin Matthews and Lillian Garret-Groag. Antaeus has a rotating artistic leadership model and continues to thrive creatively. The same can be said of Kevin Carr and Kitty Felde’s Theatre of NOTE. Mako’s East West Players has also navigated its way through a series of artistic directors and, like A Noise Within, Los Angeles Actors’ Theatre, and The Colony Theatre, evolved from a 99-seat theater into a mid-size venue.

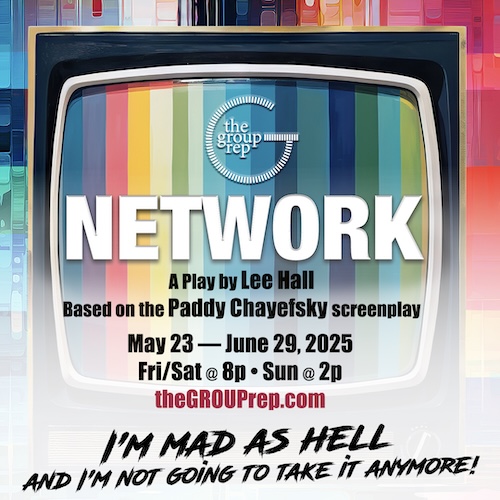

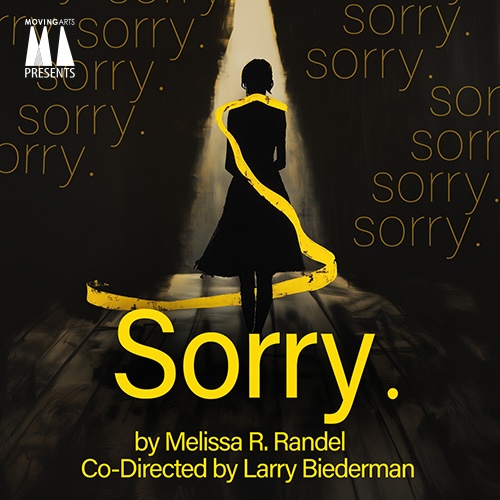

Other companies with long and storied histories here that continue to chug along include Company of Angels, Lonny Chapman’s Group Repertory Theatre, Moving Arts, Theatre Forty, and The Santa Monica Playhouse.

Dakin Matthews and Lillian Garret-Groag’s The Antaeus Company, in residence at the Taper for their production of “The Wood Demon” (1994). Davidson invited The Antaeus Company to perform at the Taper after being unable to form an in-house classical repertory company there.

Often overlooked are the newspaper writers who felt the creative energy of these times, and reported on it, thereby giving it the credence and credibility that it warranted, despite the oft-repeated platitude that live theater has no meaning in a movie town. In the Los Angeles Times, the legacy journalists who helped forge the initial recognition of our community included Dan Sullivan, Sylvie Drake, Don Shirley, Michael Phillips, F. Kathleen Foley, Daryl H. Miller, Philip Brandes and David Nichols. At the Los Angeles Herald Examiner were Charles Marowitz, Jack Viertel, Gardner McKay, and Richard Stayton, and over at DramaLogue were Lee Melville. T.H. McCulloh (who also wrote for the Times), and Polly Warfield; and Travis Michael Holder at Backstage West. At L.A. Weekly were my former-and-present colleagues Steven Mikulan, Bill Raden, Deborah Klugman, Martín Hernández, Lovell Estell III, Erin Aubry Kaplan, Judith Lewis, Neal Weaver, Tom Provenzano, and Paul Birchall (who also wrote for the L.A. Reader), and Amy Nicholson who started as a theater intern before writing film reviews for the L.A. Times and the New York Times.

At the Downtown News and Back Stage West was Rob Weinert-Kendt (now editor at American Theatre Magazine). At the Downtown News and Variety was Charles Isherwood, who skipped town to report on theater for The New York Times. Also at Variety was Bob Verini, Terry Morgan, and veteran drama critic Bill Edwards, who (in)famously knitted while sitting in the front row watching performances he was reviewing. Myron Meisel covered local theater for The Hollywood Reporter. And so on.

All of this illustrates the decades-long energy by countless individuals who have forged a theater scene that continues to be potent, despite seemingly intractable obstacles that include the soaring cost of real estate, shifting stage union policies, new labor laws, and the collapse of arts coverage in whatever scraps of print media are left.

At the pinnacle of all this activity were two giants, artistic directors at the Odyssey Theatre and the founding artistic director of the Mark Taper Forum, Ron Sossi and Gordon Davidson, respectively.

This is not written merely to traffic in nostalgia, though historical remembrances tend to lean in that direction. Underscoring that rose-colored-glasses wistfulness is the empirical reality that when Ron Sossi was building the Odyssey Theatre, Los Angeles was an affordable place for artists to live. Rents for one-bedroom apartments at that time ranged from $300 to $500 month. Those same apartments now go for $2,300/month, on average. Wages have not similarly quintupled and sextupled in that 60-year span. Not even close.

And this is why, when Sossi was first devising work with his ensembles, inspired by the work of Polish auteur Jerzy Grotowski, he could persuade his actors, through some combination of authoritarianism and charisma, that their rehearsing months on end as volunteers was part of a higher calling. That argument became harder to make with actors who, 20 years later, were now doubling and tripling up in apartments or houses and working three jobs to make their share of the rent (when they didn’t land a role in a rare, lucrative commercial). It was a harder argument to make in a new economy of income inequality, that this higher calling was a sensible proposition. In fact, because Sossi’s work was so rehearsal-intensive (as opposed to the more traditional model of rehearsing four weeks and then starting previews), and because the 99-Seat Contract of the stage actors’ union (Actors Equity Association, or AEA) permitted stipends for performances but no compensation for rehearsals, Sossi became a flashpoint in the union’s dismantling of that contract circa 2015.

Sossi and Davidson operated on opposite sides of town — literally. The Odyssey was in West L.A.; the Taper was part of The Music Center edifice in downtown L.A. The former was a scrappy 99-seat-theater dependent on a considerable amount of unpaid labor. Its longevity was a consequence of the stage actors’ union’s “Waiver” permitting union actors to perform for stipends (and with no rehearsal pay) providing that the theaters they worked in had a seating capacity that did not exceed 99.

Sossi and Davidson operated on opposite sides of town — literally. The Odyssey was in West L.A.; the Taper was part of The Music Center edifice in downtown L.A. The former was a scrappy 99-seat-theater dependent on a considerable amount of unpaid labor. Its longevity was a consequence of the stage actors’ union’s “Waiver” permitting union actors to perform for stipends (and with no rehearsal pay) providing that the theaters they worked in had a seating capacity that did not exceed 99.

The Taper was a 739-seat cultural monument that opened in 1967 and was buoyed by the fiscal generosity of movie moguls and philanthropists such as Lew Wasserman and Dorothy Chandler, government grants and foundations. Whereas Sossi was a TV producer who held a rarefied vision for the theater, Davidson was a theatrical stage manager imported from New York in the mid 1960s by John Housman for a temporary assignment to work at and then direct plays for his resident company at UCLA. When Dorothy Chandler observed one of Davidson’s productions, she invited him to run the still-under-construction Mark Taper Forum, imagined as a multi-purpose hall for community meetings, concerts and plays. Among the reasons Housman encouraged Davidson to relocate and take the job in Los Angeles was that he’d get considerable attention as a theater-maker, since there was almost no other theatrical activity in Los Angeles at the time. Like the Odyssey, the Taper was a scrappy theater in its early years, despite being located in downtown’s sumptuous Music Center. It’s possible that Davidson borrowed funds for the upcoming season to pay for the current one, according to staff who worked there in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Davidson and Sossi’s paths converged less in person as in principle. Both men wanted to form professional repertory companies. This proved to be more of a challenge than either of them imagined, even on opposite sides of their financial equations. Sossi tried to build devised works over a long rehearsal period with volunteer actors. When a handful of those actors would bolt in order to take paid TV and film work (and the medical insurance that might come with those union contracts), the ensemble would fall apart. This was an era in which the Matrix and Antaeus companies (both operating under the 99-Seat Contract) were double-casting entire productions to secure the integrity of their productions. This is not to be confused with using understudies. This was having two casts for each show, a minor nightmare for a director, and a practice derided by critics such as Charles Marowitz as an indicator that theater in Los Angeles was an unserious activity when actors could not be relied upon to hang around for the run of a production.

Yet when Gordon Davidson attempted a similar task at the Taper, to form not an ensemble for devised work but a classical repertory company with actors paid union wages for rehearsals and performances, and with health benefits, for the span of a full season, he also couldn’t hold it together. (William Ball was more successful at this at his American Conservatory Theatre in San Francisco.) This was because, as Davidson told me after he retired, being in Los Angeles, some of his actors would also bolt mid-rehearsal to take more lucrative work in film and TV. (AEA’s contract permitted its members to step away from productions, even in professional regional theaters such as the Taper, to take better paying work. And they did.)

Sossi was unremittingly dedicated to the quality of the work on his stages. The enemy of the theater is mediocrity, he once told me. Mediocrity was a quality he would not countenance. And his disregard for what he perceived to be mediocre allowed no room for the feelings of playwrights or actors, or their labors.

Norbert Weisser in Samuel Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape,” directed by Ron Sossi at the Odyssey Theatre, 2017 (Photo, courtesy Odyssey Theatre Ensemble)

I first met him when I was a young playwright, long before I became a theater critic. I’d written a one-woman show that received stellar reviews in Northern California, and I was enamored of this Odyssey Theatre in West L.A. The actress and I got an appointment to present the show to him at the Odyssey’s then-venue on Ohio and Bundy. The play concerned the emotional collapse of a housewife facing an existential crisis about her life, and its future prospects. The play was far too influenced by the writing of Samuel Beckett for its own good; still, I thought this might be a selling point for this producer so struck by the Theater of the Absurd and enamored of works from France and Eastern Europe.

The actress performed the 45 minute play on the bare stage, her character animated and despondent, while Sossi sat in the theater’s third row, attentive, expressionless. She concluded with the play’s melancholy closing speech, which I imagined to be quite moving.

There was a silence in the room. Nobody stirred, until Sossi rose from his seat, crossed through the aisle, looked at the actress for a moment. Then he looked at me. “That was cute,” he said, before walking out of the theater. And that was that.

I didn’t meet him again until years later, when I was a critic for the L.A. Weekly, and he didn’t seem to remember me, or our first encounter. It should go without saying that I never brought it up.

As I got to know him better, I realized he was a man of many qualities. At the time that the stage actors’ union was dismantling the 99-Seat Contract, and Sossi’s Odyssey Theatre was “Exhibit A” for taking advantage of actors, I know he was furious. I could feel it, in his social media posts and in conversations with him, but he was also a wise man, quick to laugh and quick to shrug. His life-preserving principle went something like, “Well, that’s the way it is. We do the best we can with what we’ve got,” and then a shrug.

He was accused by AEA and its supporters of being a profiteer because his final venue was a Los Angeles city-owned abandoned warehouse which he leased for $1 a month from the city. Why then, couldn’t he pay actors to rehearse? The stories then emerged about the shows that had been rehearsed by actors working gratis in productions that never opened. Or roles that were cut from a production during previews.

Well, to start, Sossi personally financed the conversion of that warehouse into a multi-theater complex. His other argument, which I’ve heard echoed by Latino Theater Company’s Jose Luis Valenzuela, who also manages a city-owned property for a bargain-basement lease, is that to keep a theater complex up to code, with safe electricity, safe plumbing, replacing roofs that leak, elevators that break (in Valenzuela’s case), cleaning costs, power costs, none of this is some grand bargain for these theaters when the city offers no maintenance funds.

Sossi would sputter in anger, then shrug, then laugh, sort of. Well, that’s the way it is.

The last time I saw Ron Sossi was in the lobby of the Odyssey, late last year, before a production of Daniel Passer’s solo show, Heading into Night, A Clown Show About . . [Forgetting], an existential comedy about the onset of dementia, and its accompanying despair, performed by a clown and incorporating elements of Theatre of the Absurd. Yep, that would be Ron’s thing.

Aside from an earlier massive heart attack that had knocked the stuffing out of him, and from which he had staggered back to life, and to living, it seemed to me that he had suffered subsequent strokes, maybe small ones. I concluded this, perhaps mistakenly, from the way he approached me in the lobby, extending his arm. We shook hands, and I understood that some of his strength was diminished, though he walked on terra firma. His voice was strong. His will intact, fatigued. He gazed into my eyes. “You’ve gotten older,” he said.

We all have, I wanted to reply, but didn’t. That would be too prosaic. His theater complex, buzzing with people, built over decades, now run by longtime artistic partner Beth Hogan, is a kind of monument. As is he. As are they.

To the young, graduating from college (or not), to the new generations who might want to build a place to do theater, a company, whatever, please know that Ron and Gordon can be your spirit guides. It’s true, they had it easier than you have it now. If the Colony Theatre, A Noise Within, East West Players and Los Angeles Actors’ Theatre were 99-seat theaters today, there’s no way they could evolve into mid-size theaters, as they did in their time. They’re like the parents who were able to build a home when you can barely afford rent. Our theater reflects the country we inherit, the economy we inherit, the values we espouse.

They nonetheless had a purpose to which they were unwaveringly dedicated. There were theaters in Kosovo bombed out of existence in the 1990s. A new generation of theater-makers there took to the stage in bars and cafes, like those of “Smitty” in L.A. — Smitty from the Fifth Ward of New Orleans, hosting performers and plays at the Fifth Estate Theatre in East Hollywood, $7 a ticket including an apple cider on Kenmore Avenue. It can be done.

And it matters that you do it, if you want, and if you understand why it matters so very much, in these times, the way that Ron and Gordon understood in their times, that you take to the stage, wherever you can find one. It’s among the best — perhaps the only way — of responding to the callousness and lunacy of our age, of defying it.