Stranger Than Fiction

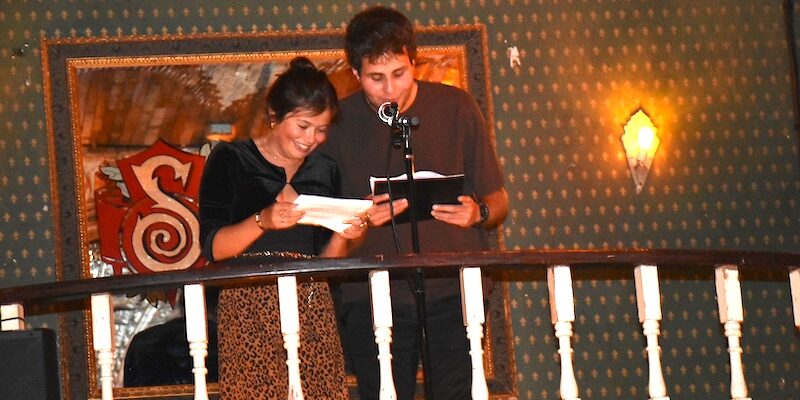

On the 60th Anniversary of Entering the United States

By Steven Leigh Morris

The Immigrants, 1963: L-R: My sister Barbara; My dad, Manning; me; My mother, Monica; and my brother, Michael

Everyone of the Boomer generation has some sense of topsy-turvey in our country, a nation that, partly, has become an inversion of its former self, and in other ways is merely continuing along an established trajectory. I write this because for me, America through the Looking Glass comes on the anniversary of my arrival on these shores 60 years ago. Sixty years. More than 80 percent of the people who were around then are gone now. Grandparents, parents, friends, lovers. So many faces in the sepia-toned photographs of my childhood are ghosts now. Sometimes vexingly, usually tempered by melancholy, anniversaries stir the dead.

I don’t have many memories of growing up the UK, since I left there when I was child, but among them were posters in windows of suburban homes in Worthing, England, in 1962, with what’s become the timeless Peace Sign. I didn’t know then that this emblem, which became glued to the Hippie counterculture movement years later in the US, was actually designed in 1958 for the British nuclear disarmament movement. I observed it in those windows next to the slogan, “Ban the Bomb.”

Nor did I comprehend at the time the gravity of the Soviet Union’s determination to install launching pads for nuclear missiles they shipped to Cuba, in 1962, on the doorstep of the United States. Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro asked Russia to help Cuba deter any more U.S. invasions of his island. The Soviets, in granting Castro’s request, were also responding to the U.S.’s newly installed missiles in Italy and Turkey, which were pointed at Moscow. The ensuing game of chicken between Soviet Premiere Nikita Khrushchev and U.S. President John F. Kennedy came in the form of a naval “quarantine” (euphemism for “blockade”), announced by Kennedy in a speech to the nation on October 22, 1962, in order to prevent any ships carrying “offensive weapons” from docking in Havana. (Eleven months later, Kennedy would be shot dead while riding in a motorcade on the streets of Dallas, a reminder even then that the United States had always been a nation of guns, and of vigilante violence as a potential remedy for grievance.)

Meanwhile, Khrushchev had announced that any interference with Soviet ships would be interpreted as an act of war. Shortly thereafter, Soviet and U.S. ships faced off. I remember the discussions in my family and my Worthing neighborhood, terrified and despairing words pointing to a second nuclear apocalypse (Hiroshima and Nagasaki were still in vivid, living memory) but this time it would be in everybody’s back yard. That apocalypse was, in fact, on the verge. The avoidance of disaster was negotiated by diplomats all dancing on the head of a pin. And we keep spitting out the phrases “existential threat” and “unprecedented” as though this is all something new.

On August 14, 1963, my parents (then in their early to mid-30s), my kid sister and older brother, all of us with luggage and Green Cards in tow, boarded a massive ocean liner owned by Pacific and Orient Lines, named the S.S. Oriana. She was docked at the Port of Southampton, England, the only country we’d ever known. We were all embarking, quite daringly it seems in retrospect, for a new life, leaving behind forever the suburbs of England, where we’d all grown up. For reasons of economic hardship in the UK, and the stultifying lack of promise there, my parents had chosen to cross two oceans on a one-way boat ride to a land unknown — the United States. My mother was particularly bonded to her mother. Her parents had driven us to the Port of Southampton, and one memory of this then 9-year-old boy is enshrined: The five of us leaning over a ship railing, stories high, looking down upon a dock platform where groups of people stood waving their farewells to the passengers. Keep in mind, this was 1963. A telephone call across the Atlantic Ocean was wildly expensive and technically byzantine. A visit between the U.S. and the UK was, for our clan, an event that had to be planned months in advance. This was an era in which such ocean crossings signified goodbye.

On the dock, amidst the throng, pushing forward, were my mom’s parents, waving, as though cheerful. My grandfather bit his lip to prevent tears. My grandmother just smiled, a mask covering anguish, as only the British can pull off. To be glib, the scene could have been plucked from BritBox.

There was a blast of the ship’s horn that I imagined could be heard across all of Great Britain. Smoke churned and wafted from two massive chimneys, and this iron whale slipped, ever so slowly, away from port, which grew smaller, and smaller, like England herself, until the island was no longer visible. Or let’s just say, it soon became unrecognizable.

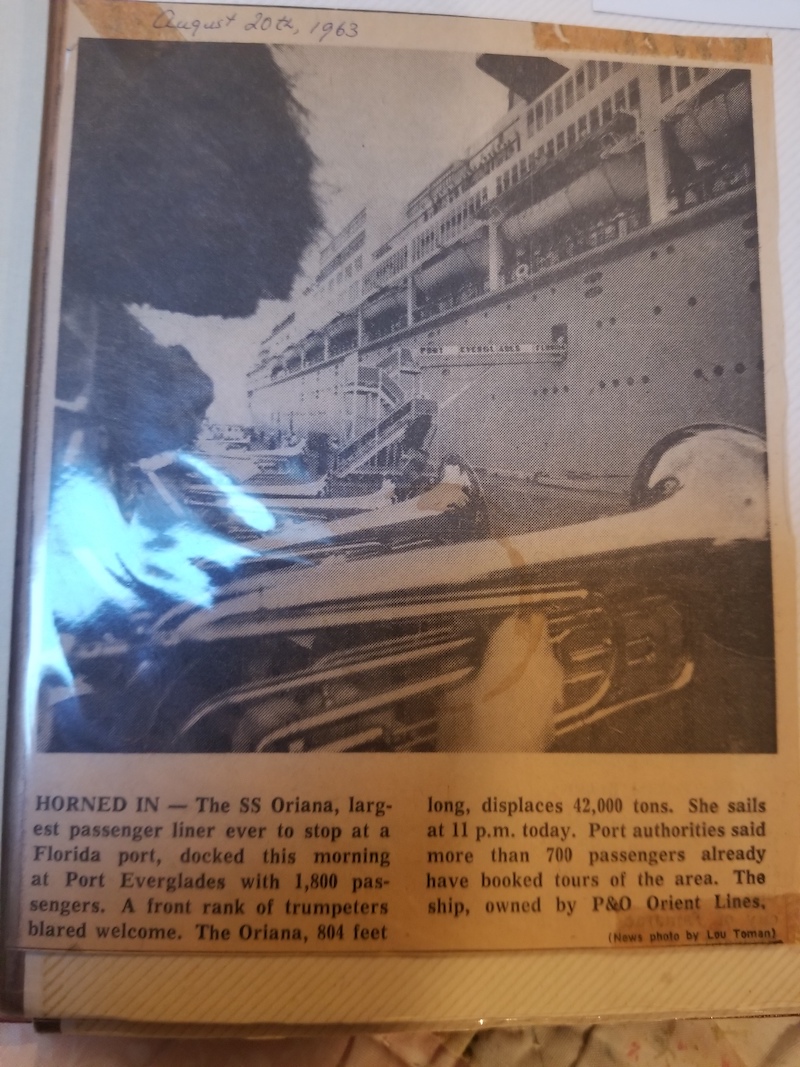

I recall for days expanses of ocean on all sides. And nothing else. Until the tiny island of Bermuda appeared on the horizon. The ship was bound for San Francisco, so there were no Ellis Islands or Statues of Liberty on our route. Rather, the boat slipped through the mighty Atlantic south of all that. I had no idea we were at a latitude somewhere between the Carolinas, which lay due west a mere 600 miles The Oriana was far too large to come anywhere close to Bermuda. It dropped anchor half a mile out, and ferries took us ashore. I remember palm trees, which I’d never seen, and felt heat I’d never before felt. At end of day, the great ship pulled up anchor and traversed further south, entering the United States on August 20 at Port Everglades, Florida.

The Oriana was at that time the largest passenger liner ever to dock at a Florida port. A banner over a loading dock shouted “Welcome, Oriana!” next to a Union Jack, while a marching band dressed in the costumes of the Royal Grenadier Guards belted out a jazzy rendition of “All Or Nothing at All,” a spectacle that my musician father found singularly delightful.

The task was to get this ship over to the Pacific Ocean, so the most direct route was to sail from Florida, around Cuba, and slip across Central America through the Panama Canal.

The Panama Canal, 1963

Cuba. There was no way we could get to the Panama Canal without floating around Cuba. Ten months prior, civilization almost ended because of what unfolded on these seas around Cuba. I was oblivious to all that. I was 9.

On August 28, 1963, we re-entered the United States in Long Beach, California, where our documents were processed. No longer migrants, we were now immigrants. My dad took my brother and me to Disneyland, while my mom stayed on board with my baby sister, who was now screaming her upset over the daily time changes that play havoc on an infant’s bio-rhythms.

My mom and my sister, on board the Oriana

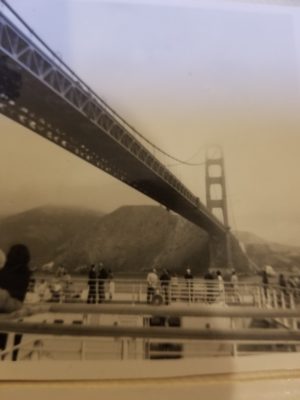

The following day, we sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge into the Port of San Francisco, where we were met by our distant cousins, a couple in their 60s, who had visited us in England, and were now sponsoring us, which meant they vouched to the government that they would support us financially if we were in danger of becoming wards of the state. That’s how we got our Green Cards.

The following day, we sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge into the Port of San Francisco, where we were met by our distant cousins, a couple in their 60s, who had visited us in England, and were now sponsoring us, which meant they vouched to the government that they would support us financially if we were in danger of becoming wards of the state. That’s how we got our Green Cards.

Floating under the Golden Gate Bridge, 1963

Cousins and Commies

Our cousins, Joe and Sheba Rapoport, took us to their chicken farm in Sonoma County, located on a back road in a tiny town called Cotati, in rolling hills of California oak about 60 miles north of San Francisco. On seven and a half acres, five barns held 15,000 Rhode Island red meat chickens, two or three steers grazed under a grove of eucalyptus trees, and a single, looming acacia tree sent out a massive spray of fragrant gold in the spring.

Biography of Joe Rapport, written by Kenneth Kann

The property contained two houses for humans, one of them vacant. This was to be ours.

Joe and Sheba were exiles from a couple of places. In 1919, in the wake of the Russian Revolution two years prior, a particularly vicious anti-Semitic pogrom drove them from their respective villages in Ukraine (then Soviet territory), on either side of the Dnieper River. Among the ironies of history, the then fledgling Soviet Red Army contained local Jewish regiments. Joe enlisted in one of them, aiming to protect Ukraine’s persecuted Jewish residents. The irony is that Joe’s service in the Red Army was the primary cause of Joe and Sheba being closely monitored by the FBI in the United States for the remainder of their lives.

Joe and Sheba met in a synagogue in the Moldavian city of Kishinev, while they were fleeing Ukraine. The synagogue served as kind of refuge station for an underground railroad transporting persecuted Jews to the United States. It was Joe and Sheba who arrived in the United States through Ellis Island, not us. It was Joe and Sheba who saw first-hand the Statue of Liberty beckoning immigrants tortured by the nightmarish circumstances of foreign countries, not us. We had not been tortured by anybody, or anything, other than a British economy and country that seemed, to my parents, to offer scant prospects for social mobility. Looking now at the various successes grasped by my English cousins who stayed behind, my parents were mistaken. But that’s a different story.

In New York City, Joe and Sheba took it on themselves to organize garment workers — among whom they worked for below-subsistence wages — into labor unions. This was another point of interest for the FBI. At a time in the United States following World War II, with the ascent of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and his henchman, Joseph McCarthy — soon to become Senator Joseph McCarthy, head hunter of the maniacal anti-Communist witch hunts — it was the worst time in this country to be labeled a communist, or communist sympathizer. (Even when I was a fourth grader at Cotati Elementary School, a decade later, the word “communist” was still electric. One dare not even say it, let alone be it.)

A settlement was reached for Joe, Sheba and their cadre of compatriots: They would leave New York for an isolated rural outpost in Northern California, where they could do no harm; they could raise chickens for a living. Joe and Sheba hated chickens, and chicken farming. They all did, these Yiddish-speaking liberals, who forged their own community and were dubbed “radicals” for following musicians such as Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, and for believing in racial integration and labor unions.

To be fair to the FBI, Sheba, for a time, spoke warmly of Joseph Stalin. It was only later that a younger generation persuaded her that Stalin was far, far from angelic, that he was in fact a genocidal maniac and that she was in a cult for being blind to the horrors of his actions. They successfully convinced her to abandon that cult. In her later years, she was quiet on the topic of Joseph Stalin, though she always had a soft spot for Vladimir Lenin.

The FBI had both Joe and Sheba on a kind of terrorist watch list, and every year an FBI agent would knock on their door to ask questions: Where had they traveled, what had they been doing in the past 12 months. On one such visit, Sheba told them she’d been to England (a lie), to visit the Queen (obviously a lie), to enjoy tea and crumpets with Her Majesty.

The FBI had both Joe and Sheba on a kind of terrorist watch list, and every year an FBI agent would knock on their door to ask questions: Where had they traveled, what had they been doing in the past 12 months. On one such visit, Sheba told them she’d been to England (a lie), to visit the Queen (obviously a lie), to enjoy tea and crumpets with Her Majesty.

Bodega Bay, 1964, Background L to R: My mom, Monica, Joe, and Sheba. Foreground: me, my kid sister Barbara

The FBI agent, a young yet already world-weary female stopped writing in her notebook and looked at the ground; she neither laughed nor smiled, but after a silence, she walked slowly back to her Ford Fairlane and drove away, leaving a small arc of dust behind.

What do Joe and Sheba think now, their ghosts, of their homeland being bombed to smithers by the political descendants of Lenin and Stalin, who ally themselves with our MAGA crowd in the United States? What would they think now of a congresswoman from Georgia allying herself with that Russian thuggery and trying to defund the FBI and its Department of Justice for prosecuting an American would-be-Stalin Russophile who now stands criminally and empirically charged with trying to overthrow a democratic election in the United States? (Wasn’t it Stalin who famously said, “It’s not the people who vote that count, it’s the people who count the votes.”) The congresswoman from Georgia now calls the FBI a “communist” deep-state menace. I’d like to call it ironic, but words for these turns of events are impotent.

The ideologies get flipped on their heads, inverted. They’re just words, rationalizations for a brand of thuggery that’s eternal. The mob remains, epoch after epoch. The mania for persecution, for revenge for some imagined if not invented indignity. The country has not become insane. It was always insane. This is not an aberration of our times, it’s a legacy.

Our loftiest ideals, enshrined in our Declaration of Independence and our Constitution, have been at war with our actions ever since our country emerged so violently from Britain’s womb. At times our actions have honored our ideals: Our military capabilities helped crush genocidal thugs such as Adolph Hitler in Nazi Germany and Slobodan Milošević in the Balkans. But most historians, with the possible exception of Ron DeSantis, know that our record is far from spotless.

Perhaps the anguish or our times, which we often blame on social media silos and their attendant distortions and lies, is actually karmic blowback for the hubris behind our slipups: the military invasion of Iraq for reasons that turned out to be non-existent; or, to go back to the military conflict of my childhood, the War in Vietnam, prosecuted by what, today, would be called “leftist” leaders (Kennedy and LBJ) — prosecuted, in the name of democracy, in order to prop up the Vietnamese Trumps (Ngô Đình Diệm and Nguyễn Cao Kỳ), whom we favored at the time, against the wishes of most of the residents living under their yoke.

Martin Luther King protested vigorously and eloquently against that war, almost ethereally, against the damage we did, the villages we burned, the soldiers we sent who returned deranged and dysfunctional, and the hypocrisy behind those actions. Perhaps what we’re suffering now, despite the heroism before and since that made us a global beacon, is a kind of cosmic retribution, to give us a taste of our own medicine practiced overseas so may decades ago? I just don’t know.

It’s been a long wrestling match, this bout between our ideals and our actions, leaving behind broken bones and blood. May our loftiest ideals prevail, if they’re able.

Red Glow

Mt. St. Helena stands tall over Napa Valley, California

I have one other memory from arriving in America. Eleven months after the Oriana dropped anchor in San Francisco, September, 1964, I was 10 years old, and I remember it being an excruciatingly hot summer. With the aim of moving out of a house with a driveway that got so muddy it was impassable from the winter rains, by car or on foot, and a roof that leaked torrents of water into the light fixtures, my parents were building their own house in a nearby city surrounded by apple orchards, called Sebastopol (the region was visited by Russians in the 19th century, hence “Sebastopol,” the “Russian River” and “Fort Ross”), bordering the ancient Redwood forests of that region. For their new home, my parents had bought land upon a hill, with a vista that looked north over a rustic valley and down onto the city of Santa Rosa, with the backdrop of Mt. St. Helena in the distance.

On September 19, the Hanly Fire broke out on that mountain in neighboring Napa County, soon joined by the Nun’s Canyon Fire, and the Mt. George Fire. My memory is of my family looking north in the daytime to see smoke billowing up from Mt. St. Helena, miles away, but not far enough to contain their obvious apprehension. At night, the mountain flared red. At first, I was taken in by the spectacle, an enchantment soon replaced by a looming dread as the red glow roared towards Santa Rosa. They stopped it just north of the Santa Rosa city limit after 83,000 acres had been scorched, taking out 84 homes and 24 summer cottages, but remarkably no lives lost.

Nobody then, at least nobody that I knew, was talking about climate change. They all drove cars and trucks with at least eight cylinders, gas guzzlers, without a thought of its consequences.

And we keep tossing out words such as “existential crisis” and “unprecedented,” as though any of this is new.