The Darkness: Goddess Revealed

Reviewed by F. Kathleen Foley

The Actors’ Gang

Through June 17

It’s not a good sign when a critic has to read and reread the advance press materials in an anxious but sincere effort to understand a play.

After viewing The Darkness: Goddess Revealed at the Actors’ Gang, I felt as if I had witnessed something profound, powerful and very moving.

I also felt as though I had struggled with overlying philosophical concepts that were so intellectually obtuse as to be nearly indecipherable.

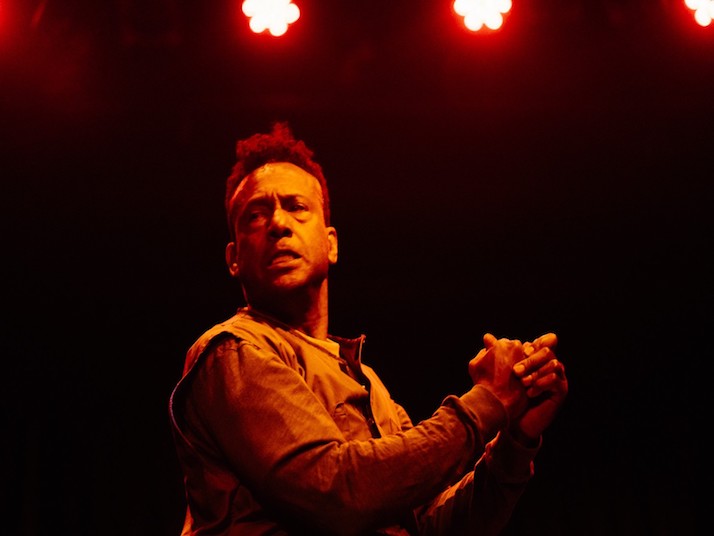

Writer Nick Gillie has essentially assembled his play into three lengthy monologues, all richly comprehensible, but punctuated by far less coherent interstitial segments.

Taut and well-written, these monologues, all performed by Gillie with astonishing intensity and craft, represent the experience of three Black men from different walks of life and historical periods. Each speaks as he enters the afterlife and is met by three spirits in Black female form (Liza Cruzat, Raquel Rosser, and Erin Nicole Washington.)

The first posthumous monologue — or more appropriately, confessional — concerns Dr. Glory Banks, a successful surgeon whose revenge-driven existence was prompted by a childhood incident in which he witnessed his father viciously beaten by a White man in his native Alabama. Since then, Glory has made the Whites who disrespected him, one in particular, the target of his conniving, often graphically sexualized reprisals — only to become an abuser himself, as monstrous as the hated White tormentor of memory.

Then we meet the “outlaw,” Patrick Bartholomey, who tells us that, while he was still just a child, he shot his father’s killer dead. That act gave him a sense of omnipotence that helped him survive a weary world, yet kept him emotionally isolated, save for one older female lover, the sole human connection in his life. His refusal to have children with her resulted in their breakup, yet he mystically reconnects with her “soul” via one of the women spirits in the Darkness, i.e., the afterlife. (I told you it got confusing.)

In the most heartbreaking reminiscence, Darrick Taylor describes his experiences as a Mississippi slave — the grinding toil, the relentless sun, and most agonizingly, the pain of having his beloved children torn away from him and sold. His humiliating public whipping and sodomizing by a White overseer is so harrowingly recapitulated, it’s hard to hear. Yet Darrick is inspired to carry on by his intrepid wife and his fellow slaves, who support him in song and lend a spiritual (no pun intended) dimension to the account.

Live drumming by Mizan Willis, projection design by Corwin Evans, A/V design by Cihan Sahin and lighting by Bosco Flanagan all effectively contribute to the otherworldly ambience of the evening, while director Dwain Perry, Gillie’s frequent collaborator, contributes a typically assured staging.

A former staff writer for American Gods, Gillie apparently intends to redress the negative connotations associated with the words “Black” and “Darkness,” and to create a new mythology based on the African American slave experience.

That’s almost certainly an oversimplification of Gillie’s worthy cause. However, it’s those interstitial segments that leave us in darkness. Are these wraiths of the afterlife the spirits of Darrick’s stolen children? Is one of them the progeny of a White abuser who must pay the penalty for the sins of her fathers? Must another remain in semi-corporeal form before she can assume her full role as one of the ethereal “We?”

We strive to understand but get lost in the weeds of Gillie’s philosophical/mythological construct, which might have been better served as a one-person play.

The Actors’ Gang, 9070 Venice Blvd., Culver City. Fri.-Sat. 8 p.m. through June 17. (310) 838-4264. boxoffice@theactorsgang.com. www.TheActorsGang.com. Running time: 90 minutes with no intermission.