Allen Barton’s play, and its connection to the cancelling of a new play at Santa Monica College

By Steven Leigh Morris

Allen Barton’s play, Outrage, directed by Barton and co-produced by Crimson Square Theatre Company and the Beverly Hills Playhouse (and presented at the latter), concerns a theater teacher/coach (of directors, actors and writers) in a private studio who, along with his wife, happens to be a Trump voter.

This is not something they brag about. It slips out. Kind of like German conductor Karl Böhm letting it slip that he voted for Hitler. (Actually Böhm’s support for Der Führer was public and unapologetic, but that may have been an instinct for self-preservation.)

This is just me, but I can’t get past this teacher’s support of Trump, whose character traits were abundantly clear in 2016, and have only gotten worse. In 2016, he simply looked like the kind of narcissist-predator-bully who relished mocking the powerless, the poor, the infirm, and anyone who critiqued him. He could thrill opponents of civility, which was his reality-TV calling. In 2023, threatening to “root out” if not murder his opponents, to turn the Justice Department into his tool for revenge, and to create concentration camps for immigrants, this is no longer just a free-speech or even a corruption concern. It’s a movie-trailer for the hellscape we could be entering should he be re-elected, or re-appointed, or however he and his enablers might finagle his political return. This is the zombie that never dies. And the zombie is not him; it’s us, and the culture that contains us, for letting this happen.

Barton has written a play of ideas, kind of, in which the teacher Ethan (the appealing Peter O’Connor) refuses to issue a statement on behalf of his theater/school opposing the judicial exoneration of a White LAPD policer officer who murdered a Black teen. His school is not a haven for virtue-signaling, he argues. His opinion of the justice system is irrelevant to his (or his school’s) task of teaching theater. A petition by his students brews against him, until he is removed from his post. Later, his theater is torched.

The object of this play’s wrath is the excesses of the Left. Whatever Left means. I’m still sorting this out, because Barton’s play (in many ways at odds with my own convictions) also contains core and unarguable truths that resonate. There’s a hole in the middle of his play, but sections of it are perversely brilliant in a fucked-up, David Mamet way.

So what exactly is left of the Left?

Liberal versus Progressive

I’ve been thinking about Gordon Davidson lately, a lot. For those of you under 40-years-old, Gordon Davidson was the founding artistic director of the Mark Taper Forum. His inaugural production there, in 1967, in the newly built theater, was John Whiting’s play, The Devils, starring Frank Langella. In that production, a character named Sewer Man (Ed Flanders) spilled slop onto the stage, staining the purple cloak costume of a libertine priest (Langella) in 17th century France. Keep in mind that the Archbishop of Los Angeles was a supporter of this new, multi-million dollar downtown theater project.

I’ve been thinking about Gordon Davidson lately, a lot. For those of you under 40-years-old, Gordon Davidson was the founding artistic director of the Mark Taper Forum. His inaugural production there, in 1967, in the newly built theater, was John Whiting’s play, The Devils, starring Frank Langella. In that production, a character named Sewer Man (Ed Flanders) spilled slop onto the stage, staining the purple cloak costume of a libertine priest (Langella) in 17th century France. Keep in mind that the Archbishop of Los Angeles was a supporter of this new, multi-million dollar downtown theater project.

Ronald Reagan was California’s governor at the time. He and his wife Nancy had attended a pre-opening party with Mayor Sam Yorty, Gregory Peck, Kirk Douglas, Alfred Hitchcock, and dozens of LA’s movie-industry and political elite. All of them were in the opening night audience.

During the first of two intermissions, the Reagans walked out, never to return to the Mark Taper Forum again. The Reagans departed with one-third of the audience. During the second intermission, a second-third of the audience made their escape, leaving just one-third of the original theater audience to applaud the theater’s debut production.

If this had happened in 2023, it is likely that Gordon Davidson would be fired within the week. In 1967, however, that didn’t happen. Davidson remained in his post for decades. Not that there wasn’t agitation to remove him in 1967. But these ambitions were quelled by the CTG Board member who hired him, Dorothy Buffum Chandler (then director of the Times Mirror Company), and CTG Board President, movie mogul Lew Wasserman.

Davidson had made the case that part of theater’s function was to shock people from their complacency — not its onlyfunction but part of the equation. Wasserman and Chandler concurred with Davidson, who, for lack of a better word, can be called a liberal.

It’s no coincidence that Ronald Reagan was among the first in the Republican pantheon of politicians to deride the word liberal, coating their intuitive affection for a caste system with charm and charisma. (It took about four decades for the charm and charisma to evaporate.)

I’m among countless people of my generation who grew squeamish at even using the word liberal, glomming on to what seemed a less toxic synonym, progressive. And I admit to being in a fog as to what that latter word even means anymore, just as the principle of the self-made person, and the virtues of small businesses, have become unglued from the meaning of the word, Republican.

Pamela Paul, in the New York Times, offers some helpful guidance on the distinctions between liberal and progressive.

Writes Paul, “Whereas liberals hold to a vision of racial integration, progressives have increasingly supported forms of racial distinction and separation, and demanded equity in outcome rather than equality of opportunity.

“Whereas most liberals want to advance equality between the sexes, many progressives seem fixated on reframing gender stereotypes as ‘gender identity’ and denying sex differences wherever they confer rights or protections expressly for women. And whereas liberals tend to aspire towards a universalist idea, in which diverse people come together across shared interests, progressives seem increasingly wedded to an identarian approach that emphasizes tribalism over the attainment of common ground.”

What Gordon Davidson did in his tenure as an artistic director was liberal. He didn’t like that his audiences were 80%+ White, and the ratio of White artists to non-White artists was even higher. And so he opened the doors of his theater to artistic representatives of non-White populations, and populations with disabilities, encouraging them to develop work in on-site laboratories, for possible presentation in the American theater. This was all grounded in a principle, firmly entrenched in 1960s liberalism and law, called equal opportunity.

When I was young, in the 1970s, I was reading treatises from what was then called “The New Left”: Herbert Marcuse, Jerry Rubin, Malcolm X. My “cousin” Joe Rapoport (who was really an older, uncle figure) had emigrated to California via New York and Ukraine. He’d fled Ukraine from anti-Semitic pogroms. He fled New York because of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunts. Joe had an F.B.I. dossier on him a mile wide because of his efforts to unionize garment workers in New York. For this, he was labeled a “radical communist” and exiled to California’s hinterlands where he spent the rest of his life raising chickens. And yet this “radical communist” railed against the books I was reading, and their calls for revolution. Joe had seen revolution up close. He had served in the Red Army to protect Jewish populations in his Ukrainian village.

Joe, a member-in-good-standing of the Old Left, preferred the writings and speeches of Cesar Chavez and Dr. Martin Luther King, of non-violent protest. “You change something on your own block,” he used to tell me, “That’s how you change the world.”

It seems to me now that the distinctions between liberal and progressive simply recycle what was then the Old Left and the New Left.

Liberals such as Gordon Davidson believed that theater, and the words and ideas it contains, is a bastion of free speech. And part of free speech is to create offense, if need be, so long as it doesn’t incite violence (which is not protected speech). Part of theater is to create offense, if need be. The progressive approach to language, on the other hand, is that speech is something from which communities need protecting, that words cause harm. And if speech causes upset to some groups, it shouldn’t be spoken. Retribution follows.

Here’s from a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion guide for the faculty of California’s Community Colleges: “Take care not to ‘weaponize’ academic freedom and academic integrity as tools to impede equity.” (Thanks to David Brooks’s “Universities are Failing at Inclusion” in the NY Times for this reference.)

Translation: Even though academic freedom is legally tethered to U.S. Constitutional First Amendment (free speech) protections, don’t try to argue it as a right on our college campuses, if it interferes with our agenda.

Santa Monica College Tells the U.S. Constitution to Take a Hike

From L to R, Farah Harris, Xcellen Connor and Kyra Surratt in a rehearsal “By The River Rivanna” at Santa Monica College. The college administration canceled the production. (Akemi Rico | The Corsair)

This brings us to the Santa Monica’s College’s day-before-opening-night cancellation of a new play, By the River Rivanna, written by Stage Raw Contributor G. Bruce Smith (a White male), and directed by Department Chair Perviz Sawoski (ethnically Parsi, a nearly extinct minority group of Iranian descent who settled in India.)

The main victim here, according to the Foundation of Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) is not so much the playwright, but the faculty member Sawoski, who researched and directed the play, commissioning Smith (a playwright-in-residence with the theater department) to write the script. The play was part of a course, hence the issue of course instructor/play director Sawoski’s academic freedom rising to the top.

According to both Smith and Sawoski, the project was part of a theater class, developed with student participation. Sawoski had visited a former slave plantation museum in North Carolina, and after extended conversations with the curator of what happened there, she felt these stories contained rich fodder for a play.

Sawoski followed standard department protocol in getting the play approved for production at the college: She pitched the idea after distributing the script throughout the theater department. It was approved for the class, and for public presentation, without dissent. (An earlier play, put on by the department, was about a Japanese-American family interned in the US during WWII, also penned by Smith. It engendered no controversy.)

For By The River Rivanna, Smith says that via the Smithsonian Museum, he watched videos to ensure the historical accuracy of speech patterns, inflections, expressions, etc. He vetted the script with two African-American consultants, an historian and a playwright, who both signed off on it. Both Smith and Sawoski understood that the topic was loaded, and hence they engaged in numerous revisions in order to remain sensitive to local audience concerns. Still, two actors dropped the course during the audition process, removing themselves from the production.

The school newspaper, Corsair, ran a story on the production, posting a copy of the still unfinished script, without Smith’s or Sawoski’s consent.

Shortly thereafter, students from the Pan-African Alliance and Black Collegians program filed a complaint with the college administration, arguing that neither Smith nor Sawoski had any right to tell this story, because of their respective ethnicities. More campus organizations piled on, organizing protests.

Campus police assured the actors that they (the police) would protect them should the protests turn violent.

The college’s President, Dr. Kathryn Jeffery (an African-American), attended a rehearsal a few days before opening. According to Smith, she told him that the play contained nothing that warranted such a controversy. (Jeffery did not respond to Stage Raw’s request for comment.)

Then an administrator announced the cancellation of the performance. Sawoski protested this decision. Meanwhile Smith contacted FIRE, which wrote to the college an urgent demand, signed by Ida Namazi, FIRE’s Program Officer for Campus Rights Advocacy, that the play be permitted to continue:

“While the play’s nature may have offended some, the First Amendment protects the faculty’s academic freedom to assign students pedagogically relevant material. Administrators must not unduly interfere with matters in the purview of SMC faculty and must therefore permit the play to go on as planned — so long as the students want to put it on.”

That last clause would seem to have triggered the administration’s subsequent actions. Two days before the scheduled opening, Jeffery arrived with trustees from the college. Sawoski says that they used three hours of the allocated four-hour rehearsal to take each actor, privately, into a room, in order to assess their feelings about the play’s content. The following night, they showed up again, this time with ballot boxes. Two votes were taken. In the first vote, the majority of students voted either to put on the play or to delay it one week, in order to facilitate conversations about the topics it raised. The faculty and students then suggested a second vote, that the play should go on not to the public, but to friends and family, since the cast had spent weeks rehearsing it. The majority of the cast approved that remedy, but enough cast members remained sufficiently cautious to render a performance impractical. The group collectively decided that they didn’t have the time to replace them before the semester would end, and so the show should be cancelled.

Administration announced that students and faculty had decided to cancel the show.

On learning of the cancellation, FIRE sent off a second letter, which could be described as a “How stupid do you think we are?” missive.

“Public college administrators may not put faculty members’ constitutionally protected exercises of academic freedom to a vote in this manner. As our first letter noted, it is settled law that the First Amendment binds public colleges like SMC, and the Supreme Court has recognized academic freedom as “a special concern to the First Amendment,” “of transcendent value to all,” in which “government should be extremely reticent to tread.

“. . . And courts side time and again with faculty even where they elect, for example, to teach material related to race or gender issues that may be highly offensive to some students. . . For example, in Hardy v. Jefferson Community College, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit rejected as “totally unpersuasive” any “argument that teachers have no First Amendment rights when teaching, or that [college authorities] can censor teacher speech.”

Santa Monica College replied, via Campus Counsel, Robert M. Myers, that it too believes in freedom of speech, but that this decision was not theirs. It was a decision of the faculty and students.

I asked FIRE that if there are circumstances wherein administration can intervene to protect student safety.

Alex Morey, Director of Campus Advocacy, said that if there are “actionable misconduct allegations” (physical or sexual assault), then administration not only has the right but the responsibility to intervene.

“Here, there were no misconduct allegations whatsoever. Instead, administrators improperly inserted themselves into the faculty members’ classroom affairs where that faculty member is, legally, in full control of the course content, materials, and instruction.

“So we don’t need to ask about the specifics of which of the interventions were unconstitutional. They all were. From the moment administrators walked into class to start interviewing students, that and everything that followed were all improper and an unconstitutional violations of professor Sawoski’s academic freedom to maintain control of the classroom.”

The case remains “active” on the FIRE website.

Outrage

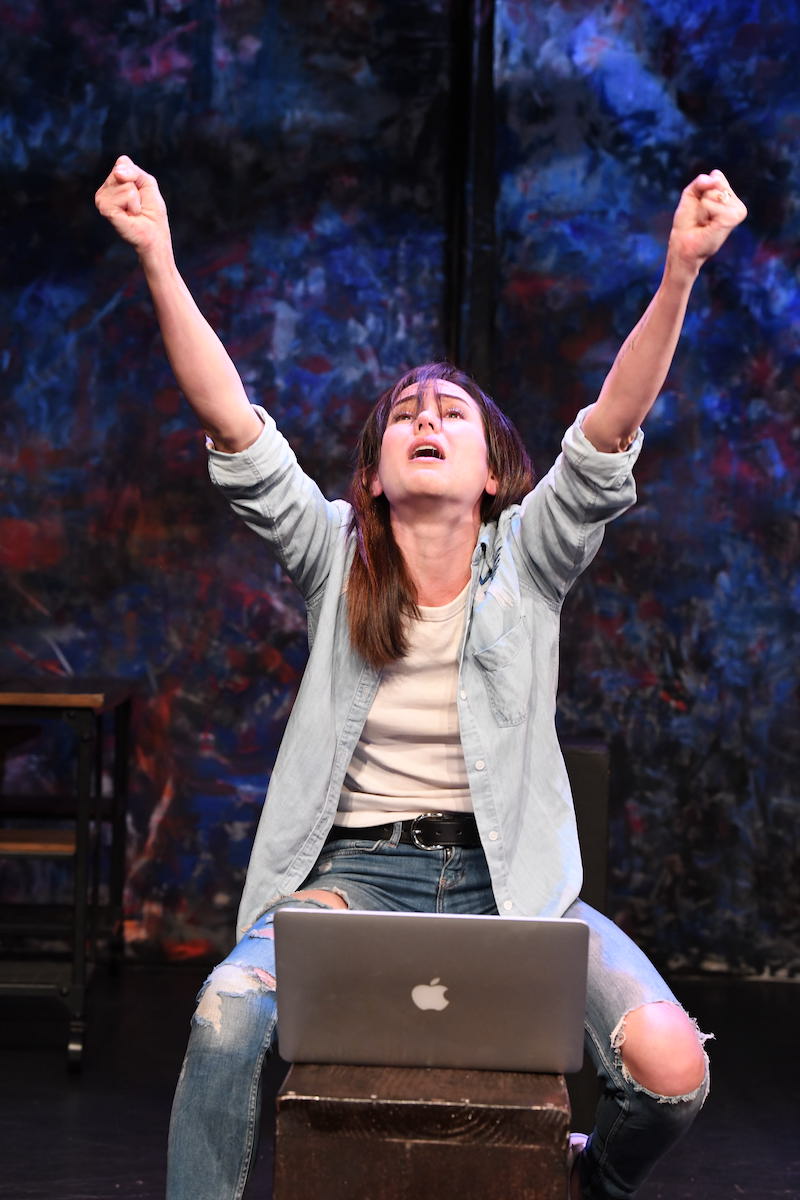

Doug (Hope Brown) trying to negotiate a truce between antagonists Ethan (Peter O’ Connor) and Tom (Kirk Fogg) in “Outrage” (Photo by Maria Proios)

This is all an inversion of how Allen Barton’s play unfolds, because Ethan’s theater gets torched, not because of what he says, but because he refuses to make a statement on a racial killing by local police that he considers to be unrelated to his school’s business. (His admission of voting for Trump doesn’t help.)

To say he doesn’t want to post on his website a political position, which everyone else is posting, is almost like a right to privacy, now in tatters. Or was it always in tatters? I recall, as a child in 1964, being compelled to recite the “pledge of allegiance” in class. It was mandated. As an immigrant from the UK, that always struck me as creepy. The country at the time was so hostile to Russia and yet it was making its kids behave with lockstep pledges, as the Russians were doing, and the Chinese. Well, like the communists. These contradictions aren’t really new. And that explains my empathetic response to Ethan’s position on privacy.

Barton’s play really gets interesting in Act 2 with three scenes, each involving characters we hadn’t yet met.

The first is an attempted reconciliation, mediated by Doug (Hope Brown), between the now emotionally threadbare Ethan and a former teacher at the school named Tom (Kirk Fogg). A scene of understated authenticity, it’s a reminder of the power of great acting. The antagonists, Ethan and Tom, loathe each other. They can barely look at each other, even as Doug strains to make some headway. Tom can’t understand Ethan’s bitterness after his theater burned down. After all, Tom had nothing to do with that. He didn’t join the cabal against Ethan. He kept to himself. And that’s the issue: Why didn’t you defend me? Slowly, slowly Tom’s rage comes to the fore — that you voted for that man. After all that he said, all that he did, the writing was on the wall, and yet you voted to destroy whatever shards of decency are left in this country. No, Tom declares, you deserved what happened to you. You’re smart, you’re erudite, you’re an artist, and yet you voted for that man.

In the absence of any substantive response from Ethan, I’m with Tom, though I’m not sure Barton wants me to be. Maybe he doesn’t care. Maybe he’s getting off on the conundrums he’s created. Not that torching a theater is ever a good thing. But yes, Ethan deserved some payback for his appalling judgment. That’s not very charitable, I know. But the nation is on fire. The world is on fire. We can no longer afford to be like Karl Böhm, voting for Hitler for expedience or any other lunatic rationale. It’s like voting for the end-times. It’s a reckless abuse of our already fragile democracy, and Ethan offers no defense of himself, or his convictions.

In the next marvelous twist, Ethan’s former student, Ryan (Evan Michael Ewing), who signed a petition against him, accidentally runs into Ethan and his wife, Lori (Cameron Meyer, in a dignified performance). Bryan appears thoroughly embarrassed and, finally, it trickles out — the apology for signing the petition that undid his teacher. He hadn’t read it, he explains. The request was for signatures to a document that he didn’t see until later. He was hoodwinked.

Ethan and Lori just stare at him. Lori takes over. And it didn’t occur to you, to say something, about this fraud that had such repercussions. Bryan mutters that he didn’t think it mattered. It was too late. The whole thing, it was so messed up.

I’m sorry, Lori continues, nostrils flaring, until Ethan calms her down: This is bullshit. This is cowardice. This is the essence of cowardice.

Here, Ethan, for once, takes the high road, telling Bryan that what he tried to do, his apology, was well-intentioned. But honestly, if we hadn’t accidentally run into each other, would you ever have said anything?

This is like an Arthur Miller scene in The Crucible or All My Sons, where conscience is put on trial with striking precision and elegance.

Miller, however, had a compass and a map of the country and the people who occupied it. Barton is more of a jokester who can cut to the souls of his characters, except, in this case, his central character. Ethan’s voting for Trump feels schematic, a means to put other issues in play. As my colleague Deborah Klugman noted, could he not at least have voted for Romney?

In the third magical scene, Ethan seeks a job in some warehouse, run by an insanely abusive, foul-mouthed Trump-voting owner, Murray (Peter Zizzo), with, let’s say anger-management issues. Zizzo turns in a knock-out, screaming performance that leaves you gaping, jaw-dropped, at his fury at wearing masks and what he perceives as the ineptitude of everyone in his company. And yet Murray and Ethan (now, so mellow) find a cause, gently, to bond, upon learning that Ethan’s theater got torched. Murray has no idea what a theater is, of what it’s for, but that it was torched by progressives stirs his poisoned little heart.

I’m so tired of living in unprecedented times. Precedented times would be welcome. Perhaps a touch of the Old Left?